With more electric cars on the road, training programs aim to get technicians up to speed

Starting this semester, White Mountains Community College is requiring its automotive technology students to take a course on electric vehicles. (Sarah Gibson / NHPR)

In the automotive technology wing of White Mountains Community College in New Hampshire, instructor Troy LaChance and his students lean over the steel frame of a half-built electric car.

Two students start to pull a cable, colored bright orange to indicate high-voltage, through the car’s floor. They’re building this car from a kit, designed by a California company as a learning tool. It looks plain: two seats, three wheels and no roof. But when they finish, the car will be able to go 60 miles an hour, powered entirely by battery.

“It’s not like it used to be,” LaChance says. “It’s not all gears and oil and a lot of mechanical stuff anymore.”

White Mountains Community College in Berlin is the first community college in New Hampshire to offer an electric vehicle technician certificate in its automotive program. And this year, LaChance is requiring all his students to take an EV class to earn their associate’s degree or certificate in automotive technology.

“I really am confident that leaving this program or even just this course gives a student the background to be able to service and work on high-voltage components,” LaChance says.

Uptake of electric vehicles is expected to increase dramatically in New England, with experts estimating over 2 million more plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and full battery electric vehicles in less than a decade. One of the big selling points for electric vehicles is that they require less maintenance. But when they do need a fix, not every mechanic knows what to do.

At minimum, LaChance says technicians should understand EV basics, including how to handle their batteries, which are about 30 times the voltage of the battery in gas engine cars. Without proper safety precautions, the electric current can be deadly.

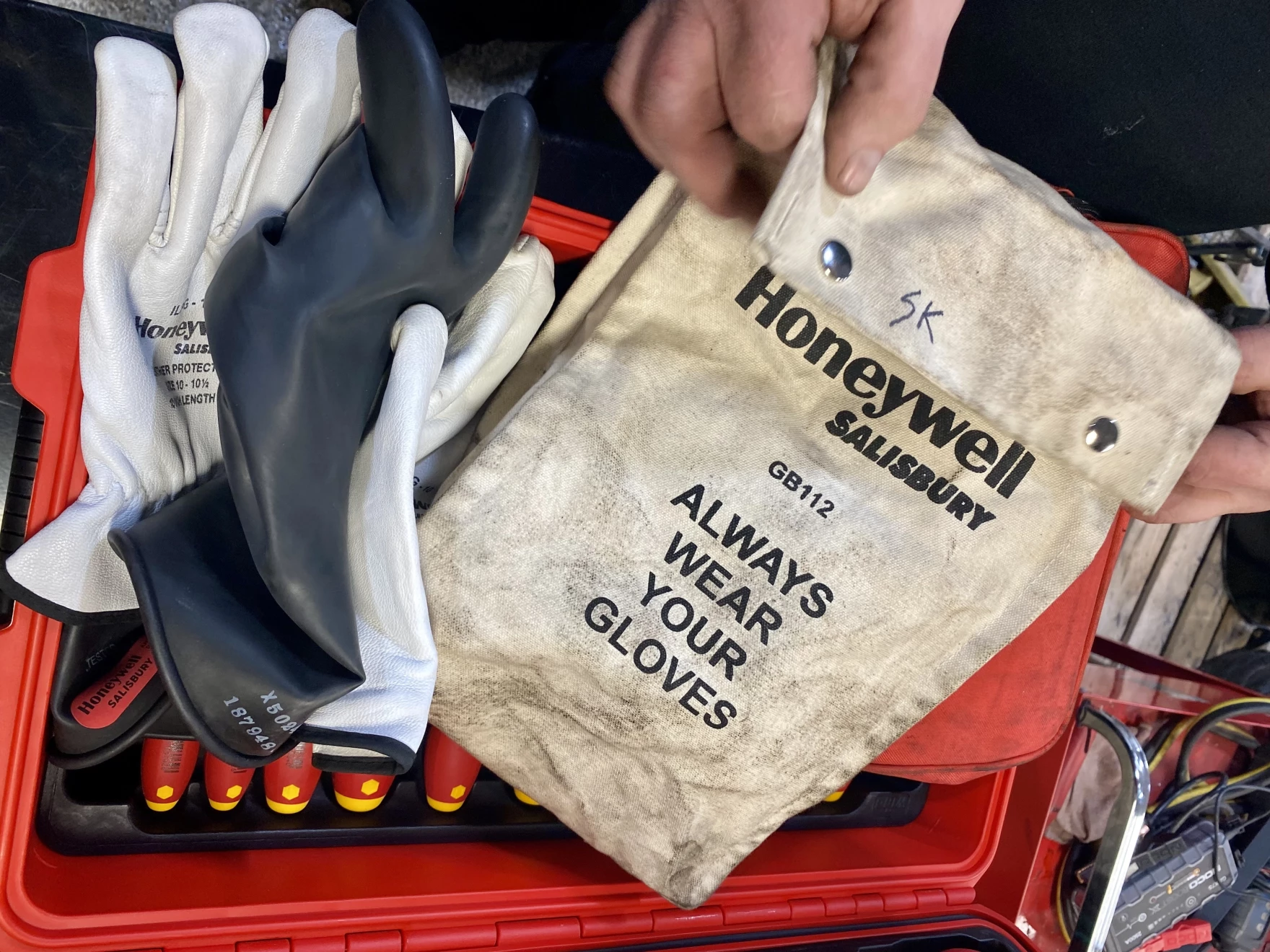

Working on an EV requires some of the same gear and safety protocol used by electricians. Here, a technician at Merchants Fleet in Hooksett holds his safety gloves, which include a rubber layer to protect against electric shock. (Sarah Gibson / NHPR)

Community colleges are an essential part of the pipeline preparing the next generation of technicians to work on electric and gas cars. But LaChance says his class sizes have been shrinking for years. This is in part a reflection of the region’s declining student population, but across the country, the auto industry is facing a shortage of early-career technicians and engineers.

Adam Memmolo, of the New Hampshire Automobile Dealers Association, says when the association last took stock of its workforce in 2016, there was a shortage of 400 technicians. Since then, he says shortages have continued if not worsened — though some local community colleges and technical education centers are starting to reverse their declining enrollment trends.

Instructor Troy LaChance and students at White Mountains Community College. The New Hampshire Department of Education has purchased six Switch EV kits for local community colleges and high school career and tech programs. The kits are designed to be built and disassembled every semester. (Sarah Gibson/ NHPR)

LaChance hopes that the EV class at White Mountains Community College — which allows students to build a car over the course of a semester — is one way to get students excited about this growing field, even if some of them arrive without any interest.

One of LaChance’s students, 22-year-old Alex Anderson of Bath, got interested in engines first with his granddad, fixing motorcycles and his 1992 Toyota Camry.

Like many technicians-in-training, he was drawn to the work in large part because of its mechanical nature.

“It’s just therapeutic in a way to put things together with your hands and have them fit somewhat nicely,” Anderson says.

Working on an EV wasn’t intuitive at first, Anderson says.

“I always made fun of electric vehicles before I did this class. I still do a little bit,” he says. “But I actually quite enjoy it.”

Alex Anderson began taking automotive classes during high school, but they were cut short by closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. He’s now in his second year at White Mountains Community College. (Sarah Gibson / NHPR)

Technicians usually get more certifications and manufacturer-specific training once they’re hired at a dealership or repair shop, says Drew Young, Director of Service at Merchants Fleet, a large used car dealership in Hooksett.

“I would almost liken it to being in the medical profession,” Young says. “Some people specialize, some people are general practitioners, some people are surgeons, and you’ve got to find out where your niche is.”

Merchants Fleet began offering a basic EV safety course and certification to technicians last year, as part of a broader effort to ramp up the EV side of its business. It’s also started offering partial reimbursements employees who buy used electric vehicles for themselves from the dealership and install home EV charging stations.

Young anticipates adding EV training to a more advanced level of the company’s apprenticeship program in future years.

But so far, Young says only a handful of his technicians have been excited to get EV-certified. Others have been reluctant, some because they prefer mechanical work to complicated electronics — and others because of their political views on climate change and the role of EVs in the country’s renewable energy transition.

Young says if New Hampshire joins the pace of nearby states in electric vehicle expansion, employers will be looking for more technicians with EV skills.

“At some point in time, internal combustion vehicles are going to become fewer and these will become more prevalent,” Young says. “And if you can’t do these, you’re not going to be as worthwhile or as valuable as an employee.”

Brian Tuttle has become indispensable in his repair shop at Grappone Ford Service in Bow for that very reason.

“I’m definitely the EV nerd here,” he says. “I’ve gotten pretty much immersed in them.”

Brian Tuttle graduated from the Ford ASSET program at Manchester Community College over thirty years ago. He’s been a Ford technician ever since. (Sarah Gibson / NHPR)

Tuttle’s been working with Ford Motor Company for 31 years, and he says Ford’s electric models have kept him engaged intellectually for at least the last decade.

But he’s in the minority. He says working on a complicated battery repair or an advanced software module is tedious and requires a different mindset.

“The mechanical nature of this business is what attracts the majority of the individuals to do this,” he says, “So the guys that really enjoy doing engine and transmission work and drive line work — [EV’s] just aren’t appealing to them.”

EV customers in the region come to this shop specifically for Tuttle, who fields detailed questions about everything from electric range to software updates.

But he wonders about who will take his place.

“Obviously, we’re not going to be around forever,” he says. “So it’s going to be a little challenging for the industry when us old guys retire.”

Tuttle says he’s placing his faith in the next generation of technicians training at nearby community colleges with strong automotive programs. And maybe, with the right teacher and class, young people will get the EV bug — just like he has.