Unburned natural gas contains 21 toxic air pollutants, study finds

A researcher takes a gas sample from a stove. (Courtesy of Brett Tyron)

There’s been a lot of focus recently on the negative health impacts of burning natural gas indoors, but a new study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology sheds light on what’s in the unburned gas piped into millions of homes across the U.S.

Researchers sampled natural gas from homes across the Greater Boston area and found 21 toxic air pollutants known to cause cancer and other health problems. While the study identified the presence of these toxics in low levels, it did not measure pollutants inside the homes or determine whether people were exposed to anything harmful.

In the U.S., “43 million homes cook with gas, another 17 million or so heat with gas. That’s a lot of end users,” says Drew Michanowicz, lead author and visiting scientist at the Harvard University T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “There’s a lot of really good reasons for us to start thinking about natural gas leaks because of climate change. We are really looking for other ways by which natural gas leaks are also directly impacting health.”

When most people think about natural gas, they likely think about methane. And for good reason — natural gas is mostly methane. Methane isn’t known to have any direct human health impacts — though given its contribution to climate change, it certainly has big indirect impacts. And with increasing evidence that gas leaks are a lot more common than anyone realized, Michanowicz says he and others wanted to know exactly what else is in the fossil fuel so many people use in their homes.

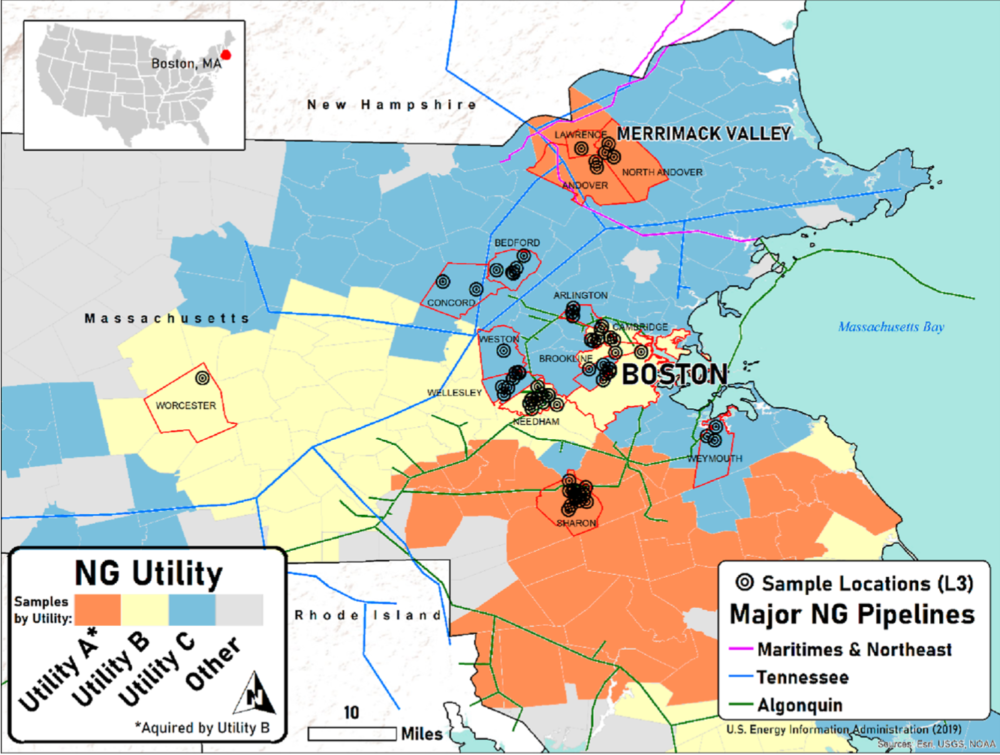

Over the course of 16 months, they tested natural gas in 69 homes across the Greater Boston region. They took samples from customers of all three major utilities, and did so several times throughout the course of the study. Those samples were then sent to a lab and analyzed for 300 trace chemicals.

Of the 21 air toxics found, the most concerning was benzene, which can cause cancer, blood disorders and other health problems. While the concentration of benzene measured was quite low, Michanowicz says the finding is important given the ubiquity of natural gas in homes.

“Because natural gas is so widely used in society and it is so widely used in our indoor spaces,” he says, “any small leaks of these hazardous air pollutants in our homes can potentially impact our health.”

The study also found considerable variation in the level of toxics present in gas at different times of year. The authors aren’t sure why, but gas delivered to peoples’ homes in the wintertime had more harmful pollutants than summertime gas. Wintertime gas also had lower levels of odorants — the sulfur compounds added to natural gas to give it a smell — though all samples met federal guidelines.

Taken together, these findings suggest that exposure to toxics may be most pronounced in the wintertime when people are already more likely to be indoors, have their windows shut and use more natural gas for heating.

This map shows where researchers sampled gas across the Greater Boston region. (Courtesy of the journal Environmental Science & Technology)

A study published earlier this year from Stanford University scientists found that gas stoves are quite leaky, and that a lot of the gas bleeds out when the stove isn’t even on. Along those lines, about 1 in 20 homes tested during this study had gas leaks that merited further inspection.

“So we have that now established in the study — that gas in Boston contains air toxics. And we know from recent studies looking at natural gas appliances that they’re leaking in homes,” says Dr. Curtis Nordgaard, a physician and one of the study’s authors. “There is a real question that we have to pursue about what does this mean for health?”

Though outside of the study’s scope, he says there probably is some risk of exposure to these toxics from natural gas, but “it may be less than other really well-established environmental health hazards like tobacco smoke.”

One big takeaway from this study, the authors say, is that we should really start thinking about leaking natural gas as not just a climate threat, but as one that may also have human health impacts. This study was meant to be the first step of figuring that out.

“Historically, natural gas has been described as a ‘clean’ or ‘cleaner’ fossil fuel. Now that we know there are small quantities of [toxics] present in the gas supply in the greater Boston area, it is reasonable to conclude that our gas supply is not as clean as we thought it was,” says Zeyneb Magavi, co-author and co-executive director of the climate nonprofit Home Energy Efficiency Team (HEET).

Dr. Regina LaRocque of the group Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility says this study “demonstrates that the gas many people cook with in their homes is a complex mixture of chemicals, many of which are dangerous to our health.

“It’s 2022, and there are now so many better ways to cook our food than by burning toxic chemicals inside our kitchens,” she said. LaRocque was not affiliated with the study.

At a recent press briefing about the study, Magavi laid out three recommendations:

- Do more to find and fix gas leaks — both indoor and outdoor leaks.

- Increase ventilation and filtration in buildings.

- Do more studies.

On this last point, the effort is already underway. Scientists are testing natural gas in homes across California and in about a half-dozen other cities throughout the country. (Though samples were only collected in the Greater Boston area, researchers say we can probably conclude that the findings would be similar in all homes and buildings connected to the same big gas pipelines in the northeast.)

Studies are also looking at whether people are being exposed to the air toxics from gas inside their homes, and whether this exposure level raises health concerns.

“It’s the potential for it leaking in a closed environment that begins to raise the question of health impact,” Magavi says. “For example, if you had a gas pump that had a small leak inside your house, it’s a very different thing than if it’s sitting outside on the asphalt leaking into the outdoor air.”

She adds that she hopes future studies will look at a wider range of known toxics and test gas at more points along the pipeline system.

This study comes amid heightened conversation in Massachusetts — and across the country — about the future of natural gas. As more and more research highlights the health and climate risks of transporting and burning this fossil fuel, many environmentalists say it’s past time we transform our energy system and stop using it.

“We are really trying to get creative and think about other ways the current system that we have is harming us in ways that we don’t know,” says lead author Michanowicz. “[We’re] trying to think about those previously unaccounted for costs. And can we can get those costs into the equation?”

This story was originally published by WBUR, a partner of the New England News Collaborative.