To solve the mystery of long COVID, researchers look to an older disease

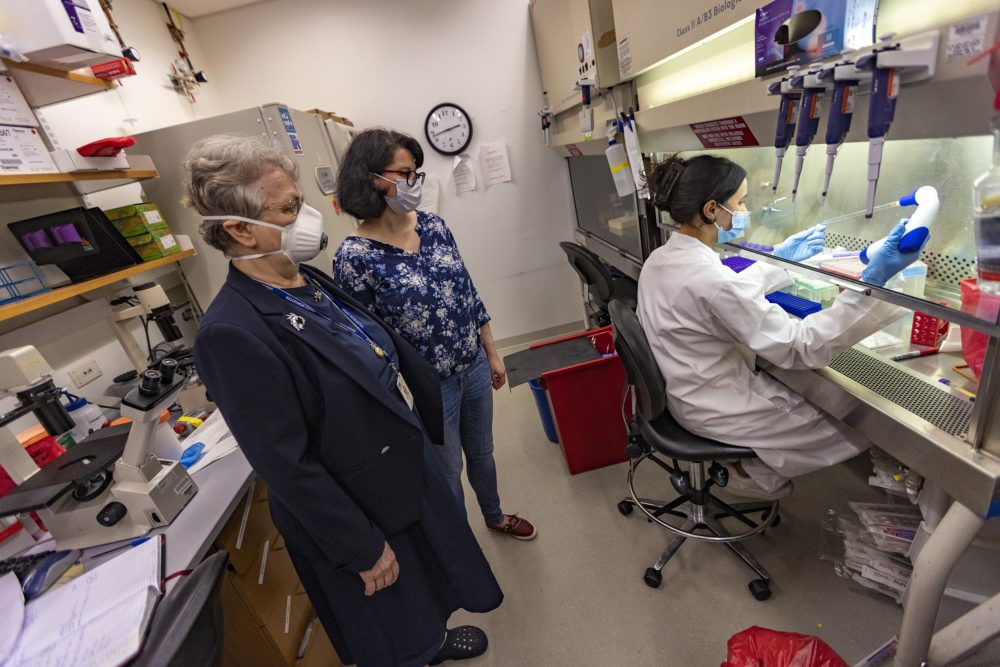

Dr. Liisa Selin and Anna Gil watch as research technician Taeva Cohen prepares blood samples for analysis in the pathology lab at the UMass Chan Medical School. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Netia McCray likes to start her day with a cup of coffee. But sometimes, making that cup can be too much.

McCray became sick with COVID more than two years ago and never fully recovered. Since then, simple tasks deplete her energy.

She still has trouble breathing, moving and thinking clearly. It takes her hours to get out of bed and ready for the day.

“When you say you’re fatigued, it’s not just, ‘Oh, I can get over it if I take a nap,’ ” said McCray, who is 32. “It’s, ‘I can’t even brew a cup of coffee that’s just a [K-Cup]’ without destroying six hours worth of energy that I know I’m going to need.”

This debilitating fatigue has become familiar to millions of Americans with long COVID.

Scientists are racing to understand it, and they’re discovering it isn’t new. The symptoms of long COVID are almost identical to a condition known for decades: ME/CFS, or myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, which causes an overwhelming fatigue that doesn’t get better with rest. Understanding the connections between these two diseases could be key to helping people suffering from both.

“They are the same disease — or very, very similar,” said Dr. Liisa Selin, a viral immunologist and professor at UMass Chan Medical School.

Selin studies the immune system. She also knows the devastating impact of chronic fatigue: She has lived with ME/CFS for 47 years.

“With every severe episode that I’ve had, I do feel like the walking dead. And I do feel like I’ve come back, basically, from being dead each time.”

DR. LIISA SELIN

When her condition flares up, she has trouble getting out of bed, walking and talking. Recovery takes time.

“With every severe episode that I’ve had, I do feel like the walking dead,” she said. “And I do feel like I’ve come back, basically, from being dead each time.”

Selin often experiments on herself. A couple years ago, she looked at a sample of her own blood and found some immune cells behaving strangely. Later, when she looked at the blood of long COVID patients, she found the same phenomenon. The immune cells appeared exhausted from working too hard.

She thinks immune cell dysregulation is causing her disease, as well as long COVID. Selin is trying to expand her research, though attracting funding is always a struggle.

“What motivates me to keep going is that I think I know the answer now,” she said. “And I really sincerely do not want other people to have the life I’ve had. If there’s anything I can do to change that, I am determined to do it.”

Dr. Liisa Selin and Anna Gil at the pathology lab at UMass Chan Medical School. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

ME/CFS affects up to 2.5 million Americans, according to the Institute of Medicine, but most of them have never been diagnosed. That’s because the disease is poorly understood. Doctors often attribute symptoms to a mental health condition like depression — instead of a problem in the body.

“ME/CFS research was definitely viewed by many as fringe and perhaps addressing a problem that didn’t exist,” said Dr. David Systrom, a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

But it’s gaining new respect as doctors and researchers realize the resemblance to long COVID. Both diseases appear to start with a viral infection. And both cause the same core symptoms: fatigue, brain fog, and periods of malaise after too much exertion.

Systrom has been testing how patients with ME/CFS and long COVID respond to exercise, and he’s observed the same nerve and blood flow problems in both.

Doctors are already using some of the same drugs to treat ME/CFS and long COVID, Systrom said. But they can only treat symptoms, such as pain and exhaustion. They can’t treat the diseases because so much about them remains a mystery.

Little is known about what causes these conditions, and why some people’s symptoms linger for so long. A better understanding of the diseases would allow doctors to prescribe more targeted and effective treatments.

Congress has authorized more than $1 billion for long COVID research. A coalition of Boston teaching hospitals is enrolling patients in studies, as part of a national initiative to learn why some people don’t recover from COVID.

It’s a big undertaking, complicated by the fact that long COVID can look different from one patient to the next. Some develop new symptoms months after their initial infection. Some experience persistent symptoms for many months. Others get better with time.

And the list of symptoms is long: fever, malaise, cough, chest pain, dizziness, disrupted sleep, diarrhea and more.

As many as 27 million Americans have long COVID, according to an estimate from the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says about 1 in 5 Americans who get COVID end up with long-term symptoms.

And new infections are still happening every day.

“We’ve seen increasing wait times for our clinic, just a continuous stream of patients who are in need of care for long COVID,” said Dr. Jason Maley, director of the critical illness and COVID-19 survivorship program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

“The demand is so high and the number of patients we’re seeing is so great that it’s a continued challenge to keep up with that need.”

Maley said he expects researchers in the coming months will begin clinical trials to test treatments for long COVID.

“The answers, I think, are going to come fast and furious. I am very heartened that whatever we find and learn from long COVID will be applicable to ME/CFS.”

DR. DONNA FELSENSTEIN

Dr. Donna Felsenstein, an infectious disease physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, is hopeful that as researchers work to untangle the links between long COVID and ME/CFS, the findings could help both groups of patients.

“With the money and the number of researchers that are now studying long COVID, the answers, I think, are going to come fast and furious,” she said.

“I am very heartened that whatever we find and learn from long COVID will be applicable to ME/CFS.”

Speed is critical. Early treatment could help patients avoid years of suffering.

Netia McCray used to work long days as founder and director of an education nonprofit, Mbadika; now she works part-time.

She used to run marathons; now a 20-minute walk is a victory.

But as McCray learns of the new research under way, she’s optimistic.

“We’re finally seeing the world’s attention to one problem,” she said, “creating warp-speed solutions that we can test and figure out how to relieve suffering.”

This story was originally published by WBUR, a partner of the New England News Collaborative.