Scorpion stingers, once thought sterile, are covered in bacteria. That could yield new antibiotics.

A giant sand scorpion fluoresces under ultraviolet light. (Matthew Graham/ECSU)

Barbara Murdoch said scorpions have had about 400 million years of survival to get things right.

“For comparison, humans have been on the planet for about 0.2 million years,” Murdoch, an associate professor at Eastern Connecticut State University, said. “There’s got to be just something about [scorpions] that is special. That they can survive through everything that’s happened over that time.”

Murdoch and a team of researchers recently collected two species of scorpions in America’s southwest. After taking the samples back to the lab and isolating DNA in their tails, they found scorpion tail-stingers – once thought to be sterile – are actually covered in bacteria.

Her team found some of those bacteria appear to be new to science. The research was published in the peer-reviewed journal PLOS ONE.

“If you can find a new source of bacteria, or novel bacteria, chances are that you’re on a roadmap toward finding novel antibiotics,” Murdoch said. “Those antibiotics could then be used to treat human infections.”

The United Nations lists antibiotic resistance as a “global threat.” And says antimicrobial resistant infections may become the leading cause of death globally by 2050.

According to the World Health Organization, antibiotic resistance is rising to dangerously high levels in all parts of the world, making a growing list of infections such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and blood poisoning all harder to treat as antibiotics become less effective.

“A lot of other studies have looked at scorpion venom for medically-important molecules,” Murdoch said. “I don’t think they’ve looked at them as a source of, potentially, new antibiotics.”

Mark Adams, a professor with the Jackson Laboratory in Farmington, Conn., was not involved in study and said the paper wasn’t designed to specifically advance antibiotic development – it was more about basic biological science. But he said it’s important for scientists to delve deeper into how groups of bacteria function in humans and in the wild.

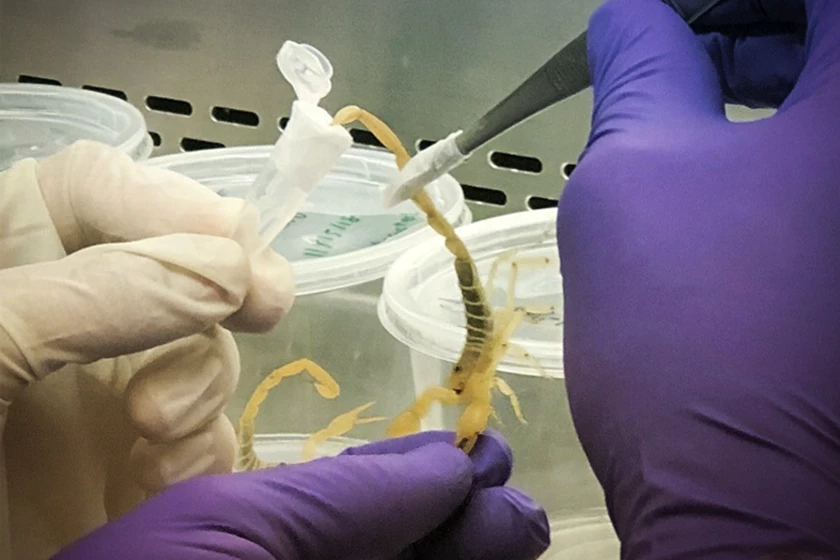

Scorpion venom is milked during an Eastern Connecticut State University study. (Barbara Murdoch/ECSU)

“Those communities and ecosystems are really complex. They’re difficult to study outside the body and they’re difficult to study inside the body,” Adams said. “The more tools we have for dissecting what those interactions look like, the better.”

He said scientists have long turned to new environments where bacteria are in competition with one another in a quest to find novel antibiotics.

“That’s not a new idea,” he said. “But the technologies that we have now available for understanding what bacteria are in these niche environments and then trying to mine them for all kinds of interesting biology – the tools are much better now than they have been in the last 10 years.”

Adams said pharmaceutical companies haven’t shown a lot of interest in recent years in developing new antibiotics, despite growing fears over antibiotic resistance.

“There’s a big health care crisis. The drug companies aren’t doing the work. And so there really is a niche for small biotech companies and for academics to try to fill those gaps,” Adams said.

Murdoch, the professor at Eastern, said it’s still not entirely clear how the bacteria on the tail stingers function – and the role they play to either protect the scorpion or, possibly, enhance its venom.

But she hopes the paper is one more step in understanding the biology of this 400-million-year-old invertebrate.

“I hope, also, that it helps people become more aware about antibiotic resistance,” she said. “And maybe look into it further to learn about things they could be doing today that could help.”