School mental health program eases transition from hospital to classroom

Karen Peters, a social worker, is the BRYT clinical director at Amherst Regional High School in Amherst, Mass., where the program is currently serving 26 students. (Ben James)

On a recent February morning, Eliza, a senior at Amherst Regional High School in Amherst, Massachusetts, walked down the school hallway. Accompanied by a school social worker, Eliza chatted about some of her favorite books and TV shows, and when she passed a teacher she hadn’t seen in several weeks, she got excited.

There was no hugging due to COVID-19, so Eliza just jumped up and down. (NEPM is using only the first names of students to protect their medical privacy.)

“Oh my god, this is my amazing Chinese teacher! I love her so much!” Eliza said. “She is so cool. I had her for all four years.”

Listen to the audio version of this story at NEPM.org.

Psychiatric hospitalizations have increased across the U.S. for teens struggling with suicidal ideation and other mental health challenges. But after they leave the hospital, teens face what’s often a daunting prospect: going back to school.

Eliza’s outgoing personality belies what for her and many high school students has been a rough couple of years. She’s among a cohort of students who struggled with anxiety and depression before 2020, and whose challenges have only grown in the context of the pandemic. This winter, Eliza was hospitalized following a suicide attempt.

“It can be really overwhelming just being in school,” Eliza said.

A unique kind of classroom

When Eliza returned to her high school, she didn’t go to her usual classes. Instead, she went straight to a classroom that’s home to Bridge for Resilient Youth in Transition (BRYT), a program designed to assist students returning to school after extended absences due to mental health challenges.

“When I came back from being hospitalized again for two weeks, BRYT was a place where I could kind of readjust to being out of the hospital and kind of delve back into being in school,” she said.

This was the second time BRYT had played a significant role in Eliza’s life.

“At the end of my freshman year I tried to commit suicide, and then once I had recovered, the next year, they put me in the program so I could have more support,” she said.

Amherst’s BRYT classroom has a mellow feel. There’s often quiet music playing from a radio. The scent of peppermint wafts from an infuser. In one corner, there’s a door leading to a small, sunny greenhouse where students can unwind. When participating students first return to school after an extended medical absence, they often spend full days in a BRYT classroom, doing schoolwork, resting or talking to counselors.

“If I didn’t have the BRYT program after freshman year, I don’t think I could say that I would be alive today,” Eliza said.

BRYT has partnerships with over 200 high schools in seven states. In addition to Amherst, other western Massachusetts schools hosting versions of the program include Holyoke High School and Frontier Regional High School in South Deerfield.

BRYT classrooms are often staffed by a clinician and an academic coordinator who collaborate to develop an individualized plan with each student. The aim is to gradually transition kids back to their full class schedule, a process that usually takes one to three months.

Karen Peters, a social worker, has been the BRYT clinical director at Amherst since the program started there in 2014. The program currently serves 26 students.

“Our goal here is to really provide a home base for students so that when they are experiencing high levels of distress, they don’t stay home,” Peters said.

High school dropout rates for students with mental illness are significantly higher than those of the general student population. A 2017 study of Canadian teens found that students struggling with depression were twice as likely to drop out as their peers without mental illness.

For Peters, it’s a priority to give kids a place to feel comfortable while they’re in school.

“Without us, these are kids that would walk out of the building,” she said. “These are kids that would end up in the bathroom by themselves.”

When Eliza approached Peters with a notebook in hand, Peters offered to walk her to class.

“This is your journal for PE class, right?” Peters asked Eliza. “Do you want me to go down there with you today since this is the first day you’re going?”

Eliza happily agreed to have Peters’ company, and she’s not alone.

Sounding an alarm on youth mental health

In November, the U.S. Surgeon General released an advisory sounding an alarm on the many ways the pandemic has worsened national trends in youth mental health that were escalating even before 2020.

“In 2019, one in three high school students and half of female students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, an overall increase of 40% from 2009,” the advisory stated.

Dr. Barry Sarvet, chairperson of the psychiatry department at Baystate Health, said feelings of despair among young people increased even further during the pandemic, and remain high.

“We’re seeing increased frequency of suicidal presentations for teenage girls as well as boys,” Sarvet said. “And then we’re seeing a lot of anxiety. Kids who are having panic attacks, kids who are extremely overwhelmed with fear, and [kids who are] also having difficulty with avoidance behaviors, like school refusal, and being afraid to go to school.”

A year ago, an unprecedented number of youth experiencing mental health crises were showing up in Baystate’s pediatric emergency department in Springfield, Massachusetts. Some kids had to wait a month or more for placement in psychiatric hospitals.

In a recent interview, Sarvet said that the situation had improved, thanks in part to two new youth psychiatric units in the region, but the kids keep coming.

“We still don’t have as many beds as we need,” Servant said. “For example, today we have nine children in our pediatric emergency department who are waiting for some kind of placement.”

Not too long ago, one of those young people needing placement was a high school student named Molly.

Last spring, after a prescription drug overdose, Molly spent four days in the emergency department. Then she was placed in an adult psychiatric ward, because that’s where providers had located an open bed. Molly asked to be moved to a teen unit, but there weren’t any spaces.

“I really wanted to change [locations], because that really traumatized me and really scared me,” she said.

Molly, who started high school in Amherst, was previously hospitalized during her sophomore year. During that period she connected strongly with Peters and the BRYT program. Eventually she and her family decided a change would be good, and she enrolled in another high school in the region, one without mental health resources like BRYT. After the most recent hospitalization, Molly returned to Amherst.

“I knew that the BRYT program was here, and I knew that I had Karen, and I was just like, ‘I want to go back to Amherst, because I need more support than I’m getting,’” she said.

Molly said at BRYT her mental health is genuinely valued, and she’s been working on coping skills with Peters, particularly how essential it is not to bottle her emotions. Things are on the up and up. She’s even enrolled in a class at Holyoke Community College.

“It’s a communications class,” Molly said. “So yeah, I’m excited about it.”

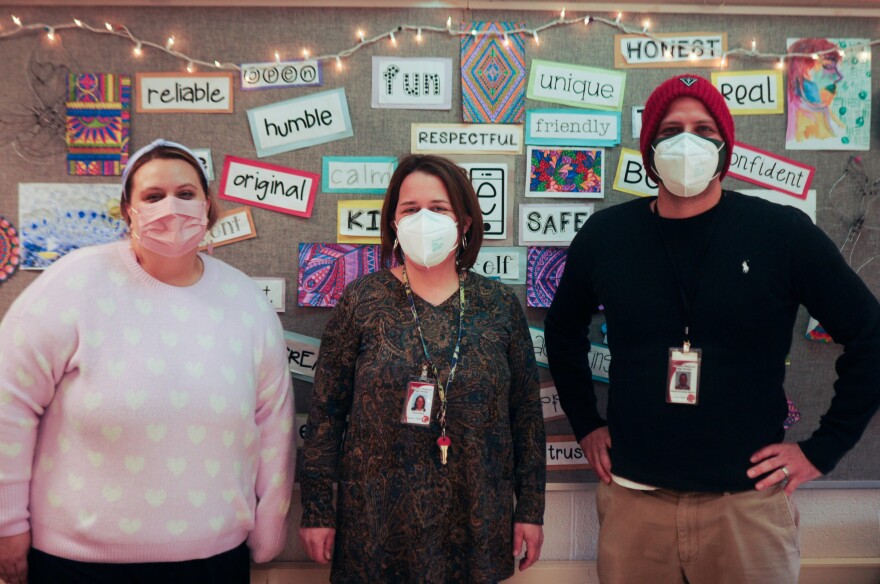

Michaela Paul (left) is a Smith College School for Social Work intern at the BRYT program at Amherst Regional High School in Amherst, Massachusetts. Karen Peters is the clinical director, and Ahmed Gonzalez is the academic coordinator for the program. (Ben James/ NEPM)

Not enough of a good thing

Demand for this level of mental health support has skyrocketed since the onset of the pandemic. Last May there were 150 schools partnering with BRYT. Now there are 230 schools serving an estimated 6,000 students, according to the program.

Peters takes satisfaction in the flexibility of her classroom, where students can even get credit for their participation (not all schools partnering with BRYT offer credit to students). For Peters, BRYT is about more than getting kids back on track academically.

“When I come down and I see a bunch of kids around a table playing a game of cards, kids who are in different social circles, or kids who will say, ‘I don’t fit anywhere,’ and they’re all around the same table — that to me feels like medicine,” she said.

The success of the BRYT model does bring challenges, however.

“The need for mental health supports is so great that there’s been a lot of pressure on these programs to work with more kids with a wider range of needs and a wider range of acuity,” said Paul Hyry-Dermith, director of the program, which is run by the Brookline Center for Community Mental Health.

Hyry-Dermith said the students BRYT serves require intensive support, and BRYT classrooms and clinicians aren’t intended to meet the mental health needs of an entire school.

“I think that everybody should have the ability to go here,” said Rob, a sophomore who’s been going to BRYT since last year, when he struggled to transition back to in-person school after months of remote education. “I think that it’s healthy.”

Rob struggles with anxiety and depression, and he’s prone to isolation. He’s one of an increasing number of students Amherst’s BRYT program is supporting before their situation becomes so acute that they need to be hospitalized.

“I go here usually in the mornings, just [to] check in,” Rob said.

Peters assists Rob in setting daily priorities and taking his own emotional temperature. She said some days it’s all he can do to get out of bed.

“Rob is also a tremendous athlete,” she added. “He’s a hockey player. His art will blow you away.”

Peters then turned to Rob.

“I am so proud of you. You work really hard to get here every day,” she said.

Rob didn’t quite smile at the compliment, just nodded and took a deep breath.

“I don’t really look forward to going to school,” he said, “but whenever I’m having a rough day, I look forward to going here, because I have people to talk to about whatever I’m going through.”

If everything goes as planned, Rob, Molly and Eliza will spend fewer hours in the BRYT classroom as their spring term progresses, but Peters made one thing clear: They are always welcome to drop in.