Rusting batteries could help power the electric grid of the future

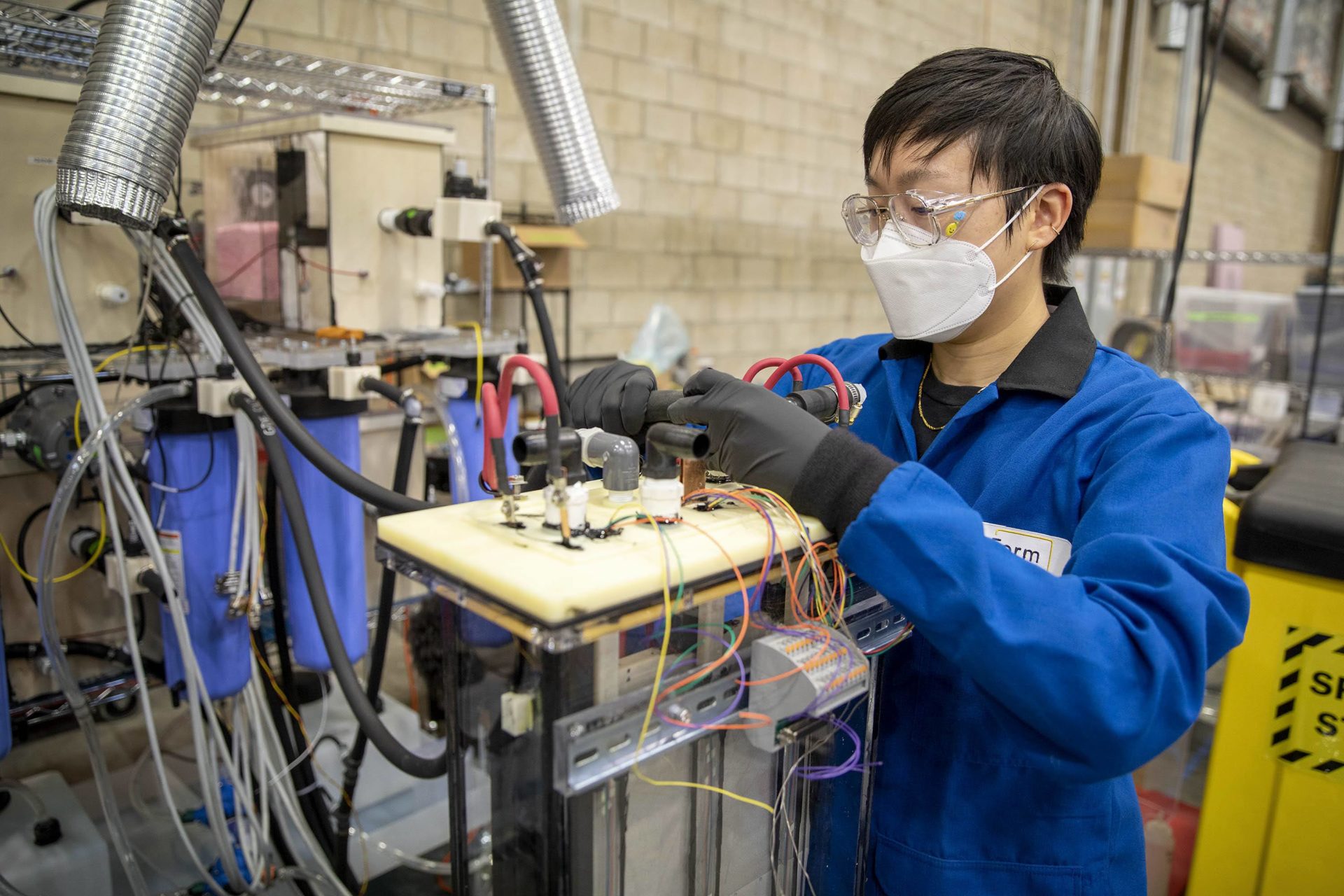

Mechanical engineer Kalina Yang prepares a section of an iron-air battery for testing. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

The same chemical process that ruins your bike chain and eats away at your outdoor grill could help power the electric grid of the future, and perhaps even help save the planet from catastrophic climate change.

Company officials from Somerville startup Form Energy are developing batteries powered by rust, and claim their low-cost, long-duration technology can store energy generated by renewable solar and wind and release it back onto the grid when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow.

President and COO Ted Wiley remembers the day five years ago he and a group of MIT scientists founded Form Energy with an audacious mission: find a low-cost way to transform the global electric system. They had a eureka moment when they thought about harnessing the rusting process to power batteries.

“My first thought was, ‘Wow, that actually is cheap enough to really have a shot at making renewable energy able to replace coal and gas everywhere in the world,’ ” he said.

Wiley became president and chief operating officer of Form Energy. Until late last year, the company operated in stealth mode. Now, they’re ready to share their work with the world.

In the company’s cavernous lab space in Somerville, Wiley removed the lid on one of the nearby 55-gallon drums to reveal the basic raw material to its secret technology.

“They’re about the size of a marble,” he said as he scooped up small, black iron pellets. Each of the drums are crammed with the balls, which are collected from iron mines around the world.

“Right now, we’re starting to establish relationships with the people who supply iron because we’re going to need a lot of it,” Wiley said.

A scoop of iron pellets, one of the cheap and abundant raw materials of iron-air batteries. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

The technology is based on oxidation, the electro-chemical process better known as rusting. When oxygen rusts iron, there’s a transfer of electrons that can be put to work in a circuit just as they can in any battery; positive flowing to negative.

Form Energy has perfected “reversible rusting” to store and release that electric energy.

“That’s the magic of what we’re doing,” Wiley said, “rusting is discharging and then, when we’re charging, we’re pushing electricity back in. We’re un-rusting it.”

The company reasoned there’s enough iron in the world, and it’s cheap enough, that it could scale to to the size of the global problem and keep electric grids, the world’s largest and most complex machines, up and running on inexhaustible, but intermittent, solar and wind.

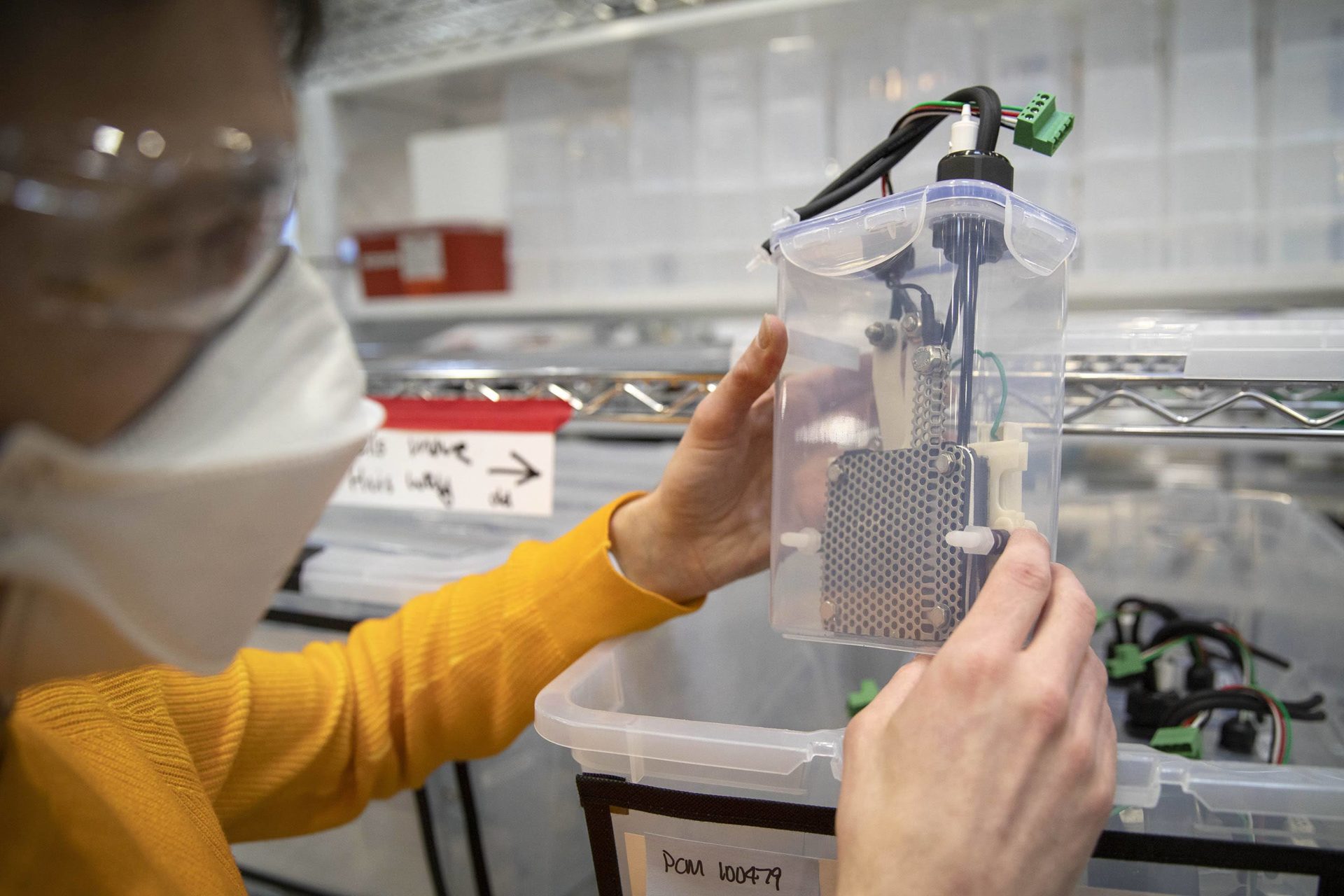

A subscale iron-air battery created for testing at Form Energy’s facility in Somerville. (Robin Lubbock/WBUR)

While the solution is cutting-edge science, it’s not totally new tech. It’s based on the iron-nickel battery Thomas Edison helped to invent in 1901. Form Energy kept the iron electrode but replaced the expensive nickel with low cost, abundant and freely available oxygen from air.

Perfecting the combination in a battery was tough. NASA and GTE scientists tried something similar in the 1960’s but gave up. The research wasn’t worth pursuing; until large scale solar and wind projects came along, there wasn’t a need for grid-scale, energy-storage technology.

The secret sauce

Inside Form Energy’s Somerville facility, researchers test prototypes of iron-air battery cells. They began with beaker-sized cells, honed the technology and are now working with full-size cells wired with sensors that providing a steady stream of data.

When they go into production next year, iron-air battery cells will be sandwiched together to form modules the size of a washing machine, which in turn can be put together to construct huge energy storage systems.

“It’s like a Big Mac,” said company co-founder and chief technology officer Bill Woodford. “You have multiple layers in the Big Mac.”

Researchers are testing different types of iron to see which perform best. Woodford said they think they found the “flavor of iron” they’re looking for, but “we are going to keep that one a secret.”

Read the rest of this story and listen to the audio version at WBUR.org.