Right whales aren’t having a good year. The pressure is on to save this hard-to-track species

It’s a chilly morning in early March. And New England Aquarium scientist Orla O’Brien and her team are preparing a small, twin propeller plane at the New Bedford Regional Airport for takeoff.

It’s perfectly clear, ideal for flying and, hopefully, for spotting North Atlantic right whales from about 1,000 feet in the air.

It hasn’t been a particularly good year for critically endangered North Atlantic right whales. Scientists have documented four right whale entanglements so far in 2023, which they say is a relatively high number for the first three months of the year. And with a population of fewer than 350 — scientists estimate the number is likely closer to 340 — the pressure is on to learn more about how and where the whales are becoming entangled.

But despite decades of research, biologists say tracking the species — and developing definitive answers about their encounters with fishing gear — are challenging tasks. And the answers that scientists have developed are often frustrating for New England fishing industries, which say the information has been used to unfairly regulate them.

For the New England Aquarium, the process starts with these monthly aerial surveys south of Martha’s Vineyard.

O’Brien points to one of two seats behind the pilot and co-pilot. “We sit there and then we’ll pop open that little square,” she explains.

And, bracing herself against the vibrating plane, O’Brien will attempt to position her digital camera out a small window to photograph the whales below.

“Sometimes they’re feeding, sometimes they’re maybe just traveling or taking really long dives, and sometimes they’re socializing,” O’Brien said.

Orla O’Brien, left, and Katherine McKenna, right, both scientists at the New England Aquarium, prepare for takeoff from the New Bedford Regional Airport on March 10, 2023. The two will fly over the Nantucket Shoals as part of the aquarium’s aerial survey program, which documents North Atlantic right whales, dolphins, sharks and other marine mammals. (Nicole Ogrysko / Maine Public)

And sometimes they can’t be seen from the plane at all. Scientists have learned that Cape Cod Bay and nearby Massachusetts waters have been a popular spot in recent years for right whales swimming north from their calving grounds along the Florida and Georgia coast to their foraging grounds off New England and Canada.

But they can be difficult to spot if they’re taking long dives, sometimes up to 40 minutes, in search of food.

“The chances of seeing one of 350 whales along the entire U.S. and Canadian seaboard is so low, it’s like a miracle that we can go out and do it at all in some respects,” O’Brien said.

But during a seven-hour flight south of Martha’s Vineyard over the Nantucket Shoals and the Rhode Island Sound, O’Brien identified two dozen right whales. An adult male that researchers have named Nimbus for the white, cloud-like shape on his right lip was part of the first group spotted.

A 15-year-old North Atlantic right whale named Nimbus was spotted off the Georgia coast on Jan. 20, 2023 with 375 feet of fishing line entangled in his mouth and dragging behind his flukes. A disentanglement team from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, along with several other organizations, managed to remove most of the rope from Nimbus’ mouth. (Courtesy Of The Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute, Taken Under NOAA Permit #24359)

“They all started popping up,” O’Brien recalled after the flight. “We worked them for a few minutes, photographed them and then they all dove again. When you think about the timing of everything, it really has to work out just right.”

In that brief window, O’Brien said she could see that Nimbus, who had been last seen entangled off the Georgia coast back in January, had now shed the remaining bit of rope that a disentanglement team had not been able to remove from his mouth.

“He certainly swam a good long distance with that gear attached,” Amy Knowlton, a senior research scientist at the Aquarium, said of Nimbus. “Had it remained attached for a long time he would not have survived. He’s fortunate that he was located and able to be disentangled.”

The New England Aquarium’s aerial survey team took this photo of Nimbus on March 10, 2023 from the window of a small plane. Nimbus was last seen entangled off the Georgia coast in January. The aerial survey team identified Nimbus by the cloud-like shape on his mouth and noticed that he was gear-free. (Courtesy Of The New England Aquarium, Taken Under NOAA Permit #25739)

But most entangled whales aren’t so lucky, because even if they’re spotted, getting a team on the water to help them is no small feat.

“Based on an average swimming speed if no one’s standing by, we have to search an area of 144 square miles,” said David Morin, a large whale biologist for the National Marine Fisheries Service, also known as NOAA Fisheries. “It’s a big whale. But it’s a much bigger ocean.”

‘It’s just rope’

Most the of the gear that is recovered from entangled right whales is taken to the gear warehouse run by NOAA Fisheries in Narragansett, Rhode Island.

Lining the shelves are black plastic bins, containing whatever rope, buoys and, in rare cases, traps, that scientists have been able to recover from large whales and other protected species.

The National Marine Fisheries Service, otherwise known as NOAA Fisheries, operates this gear warehouse in Narragansett, Rhode Island. The warehouse stores the rope and fishing gear that scientists have recovered from right whales and other protected marine mammals over the last three decades. The agency has blacked out some tags and other labels seen in this photo that may identify individual fishermen. (Courtesy Of NOAA Fisheries)

“Most of the gear is unknown rope,” Morin said. “It didn’t have marks on it. We don’t have a buoy associated with it. It’s just rope.”

The Maine lobster industry maintains that its gear hasn’t been involved in a documented right whale entanglement since 2004.

But of 1,755 entanglements that scientists have documented between 1980 and 2020, just 8% involved right whales observed carrying gear. The rest were detected based on visible scars, according to data from the New England Aquarium.

And because most recovered rope has no markings, Morin said it’s often impossible to tie an event to any fishery at all.

“When we have a piece of line that shows up that doesn’t have a mark on it, I can’t say what it is,” he said. “But I can’t rule out possible other things, either.”

The Georgia Department of Natural Resources led a disentanglement response for Nimbus, a right whale that was spotted entangled in some 375 feet of fishing line off the Georgia coast on Jan. 20, 2023. (Courtesy Of The Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission, Taken Under NOAA Permit #24359)

But since more fisheries have begun labeling their gear or have added additional color markings, Morin said federal officials are, on some occasions, beginning to learn more the origins of right whale entanglements.

At least two of the four documented cases from this year, including Nimbus, have been traced back to Canadian fisheries, according to NOAA Fisheries.

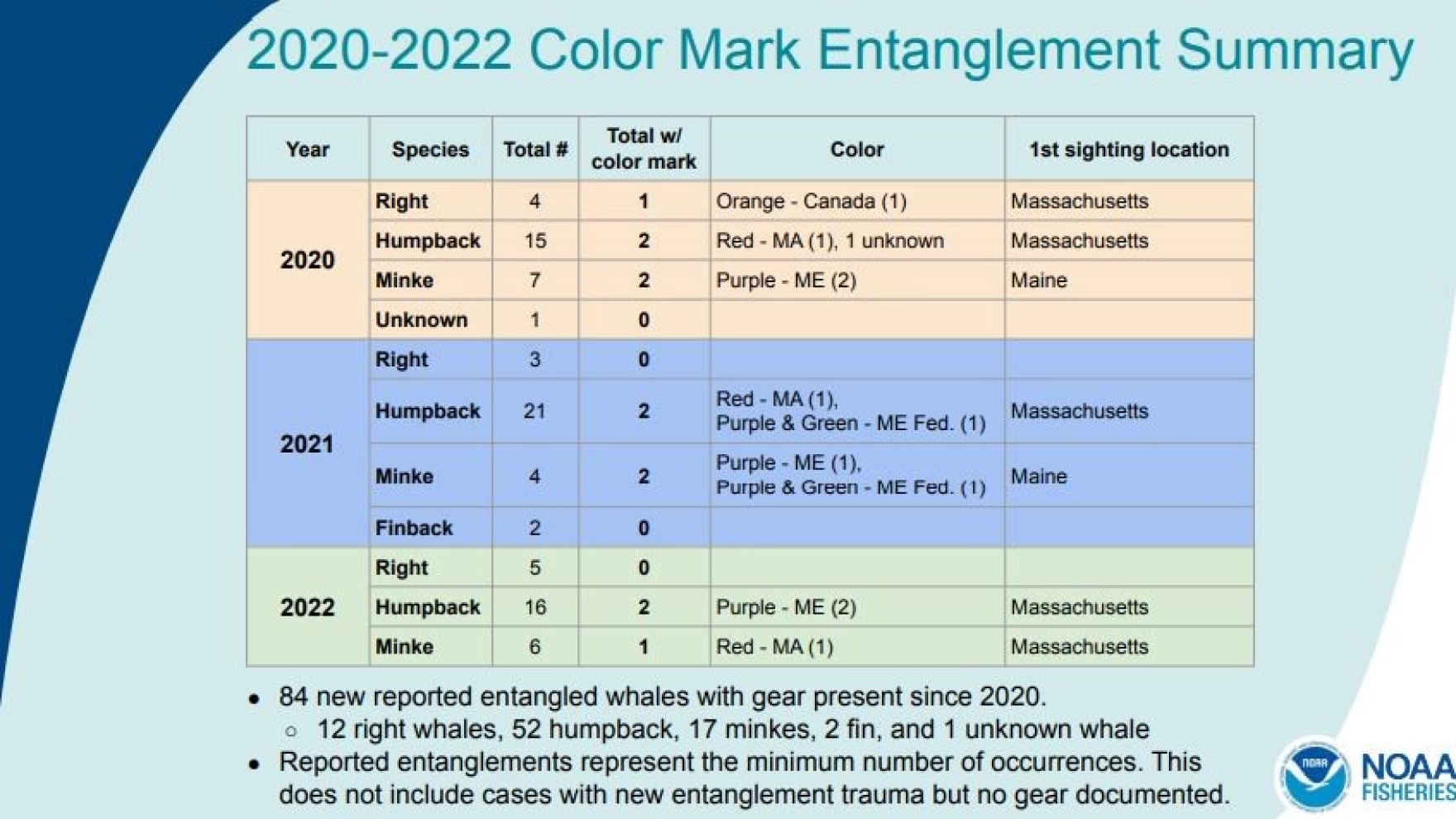

Maine made gear marking mandatory for all lobstermen about three years ago. And though Maine marks have not been found on right whales, gear with purple or purple and green markings has been recovered from at least seven large whales, including humpbacks and minkes, according to NOAA Fisheries.

(NOAA Fisheries)

“Since we added these new color marking systems back in 2019, the most common color that we’ve recovered or identified has been purple, the Maine mark,” Morin said.

Fewer whales, more gear

The majority of the estimated 900,000 vertical fishing lines in the region are found in Maine. But what’s less clear is how often right whales are swimming through prime Maine fishing grounds.

Scientists acknowledge that the Gulf of Saint Lawrence has become a more popular spot for right whales seeking cooler waters to forage, as the Gulf of Maine is now the fastest warming ocean body on the planet.

“That’s where the aerial surveys, the acoustic buoys that show that right whales are off the coast of Maine [come in],” Morin said. “Maybe not in the frequencies of Cape Cod Bay, but this then goes back to the different scenarios that you have. You’ve got a lot of whales with maybe not a lot of gear, or you’ve got a lot of gear with a little whales.”

And as fishermen try to adapt to a warming climate, scientists like Knowlton say they see more traps placed farther off shore than when studies of the right population began in earnest about 40 years ago.

“I’ve been sailing along the Maine coast for 40 years, and I’ve noticed such a dramatic change in how much gear is out there than what I used to see in the early 80s when I first started my work off the coast,” she said. “Effort has dramatically increased, and hopefully that can be part of the solution as well, removing ropes from the water column altogether — remove some fishing effort — but allow the industry to continue to do their work.”

Rob Martin, a fisherman and gear specialist who works for NOAA Fisheries, points out recovered rope intertwined with purple thread. Purple is the Maine state color, and has been found on at least seven humpback and minke whales within a three-year period. (Esta Pratt-Kielley / Maine Public)

Federal officials acknowledge they’re still learning about right whales and how frequently they’re using the Gulf of Maine. But scientists argue that the placement and volume of fishing gear can be controlled; the path that right whales take up and down the East Coast cannot.

“We’re not losing this battle because we’re not disentangling,” Morin said. “We have to find a way for the fishing industry and whales to be in the same space, to work together. That’s the only way it’s going to work, so that they don’t get these serious injuries or die from these interactions. We’re interested in seeing fishing flourish. But it’s complicated.”

For Philip Hamilton, another senior research scientist with the New England Aquarium, he used to spend his summers on a research vessel off the shores of Lubec. But as warming waters have sent right whales further off shore in search of food, a much larger, more expensive boat is now needed to track them. The aquarium is reevaluating how best to observe the population by boat, Hamilton said.

“This is probably the most dire it’s been because of the combination of changes in their food and changes in their threats,” he said. “The big question is will we reduce the harm we’re inflicting on them enough to give them the time they need to make the complete adaptation to a changing environment?

As scientists wrestle with that question, New England fisheries continue to fight regulatory efforts that they say are burdensome and unfair. Lobster and Jonah crab fisheries recently secured a six-year pause on new federal regulations designed to reduce the fisheries’ risks to right whales.

And though Maine lobstermen say they’ve already done more to protect whales by switching to weak rope, adding more traps per line and accepting the seasonal close of 1,000 square miles of prime fishing ground seasonally, the industry is battling some of those same regulations in court.

This story was originally published by Maine Public, a partner of the New England News Collaborative.