Remembering The Great Boston Molasses Flood, 100 Years Later

Firemen standing in thick molasses after the disaster. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

On a brisk winter day, Stephen Puleo, author of Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, gestured towards the spot where a tank in Boston’s North End burst, releasing a tsunami of hot molasses into the streets 100 years ago, on January 15, 1919.

“So, that green sign right there is exactly the site of the outside wall of the tank. Ships that would come up from Puerto Rico, Cuba, and the West Indies would pull up right along here. There was a pipe right here that led to the molasses tank, and they would offload gallons of molasses into the tank.”

The tank was built to be a holding vessel for molasses until it could be transported to a nearby distillery, where it was converted into industrial alcohol for World War I munitions. By the time of the flood, the war was over, and the molasses inside was expected to become rum in the last days before Prohibition.

Perched right on Boston Harbor, the tank was perfectly situated in a hub of trade activity.

“This was one of the busiest commercial sites in all of Boston,” Puleo said. “Almost all of the shipping that left Boston to go up and down the East coast, to go to Europe, left from this site. So there were deliveries all day long, this was a bustling, hustling kind of place.”

There were signs that the tank was faltering, but the people of the North End had gotten used to its instability.

“There were often comments made by people around the vicinity that this tank would shudder and groan every time it was full, and it leaked from day one. It was very customary for children of the North End to go and collect molasses with pails.”

So on the day of the flood, despite leaks and groans, no one anticipated that the tank was about to burst, unleashing a 30-foot-high wave of 2.3 million gallons of molasses that would move 35 miles an hour down Commercial Street.

“It collects and destroys buildings, people, domestic animals, stables–there are about 25 horses that are killed,” Puleo explained. “About 21 people die, 150 people injured seriously. And I’m talking injuries like broken backs, fractured skulls.”

Harry Howe was on leave from the navy for the weekend when the flood occurred. On a boat docked in the harbor, Howe witnessed the incident firsthand, as he recalled in a 1981 interview with the Stoneham Public Library: “We saw this big cloud of brown dust and dirt and a slight noise. And there was an arm sticking out from underneath the wheel of a truck. So two of us got a hold of his arm and pulled and unfortunately, we pulled his arm off.”

Howe and other sailors were some of the first people on the scene, helping with rescue efforts where they could.

Site of Molasses Disaster showing lumberyard to left near Charleston Bridge. Photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Researchers like Ronald Mayville have been fascinated by this incident, studying the causes behind it as a phenomenon of science and engineering.

Fire House No. 31, damaged by the Molasses Disaster. Photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

“No one knows exactly why it failed, but one thing is very clear: it was under-designed. Whoever did the design failed to provide the adequate thickness of the steel. On top of that, it looks like the method that they used to make the rivet-holes–the way that they put the tank together in those days was by riveting, not welding–was substandard, and that that may have created small cracks, and on top of that, the steel that they used, although it was state-of-the-art of the day, we know today that it could be relatively brittle under certain circumstances.”

It’s no wonder the tank burst. U.S. Industrial Alcohol, the company that owned the tank, had rushed to build it, employing an overseer who was an expert in finance, not engineering. When the company received complaints that the tank was leaking, it painted the tank brown to disguise the leaks rather than repair them.

Besides the structural aspects of the tank, researchers have explored how the scientific properties of the molasses itself explain why the flood was so destructive.

“It’s mostly the density of the molasses, so how much it weighs, and how tall it is,” explained Nicole Sharp, an aerospace engineer and science educator, who has studied the fluid dynamics of molasses. “You basically have a giant stack of something that’s really heavy and as soon as you remove whatever’s holding that — in this case, the walls of the tank — all of that is going to rush out, and a lot of that potential energy that you had from stacking this thing up really high is going to turn into kinetic energy. It might as well be a tsunami.”

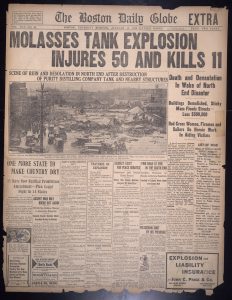

Front page news coverage of the Molasses Disaster in the Boston Daily Globe. Photo courtesy of Boston Public Library, Flickr, Creative Commons

Two days before the accident, a new shipment of hot molasses had been added to the tank, so when it burst, the molasses inside might have been slightly warmer than the outside air. As it spilled out, it cooled down and thickened, trapping survivors in the mess. Rescue efforts continued for days, and cleanup took even longer.

Immediately following the flood, 119 plaintiffs took up a civil lawsuit against U.S. Industrial Alcohol, the tank’s owner. The case was historic in many ways.

“The first case in which expert witnesses were called to a great extent: engineers, metallurgists, architects, technical people,” Puleo said. “So really kind of a landmark, important case. There were over 1,000 witnesses called in this case, 1,500 exhibits, and really kind of sets the stage for future class action lawsuits.”

Puleo described how the case’s ruling would completely change the relationship between business and government.

“There were very few regulations — public regulations, employee safety regulations — that businesses had to follow. So all the things we now take for granted in the business: that architects need to show their work, that engineers need to sign and seal their plans, that building inspectors need to come out and look at projects… All of that comes about as a result of the Great Boston Molasses Flood case.”

What’s more, the accident brought an end to what had long been a thriving industry. U.S. Industrial Alcohol never rebuilt its tank, and the company closed its Boston production plant shortly after the tank’s collapse. And for a short time, the story was all anyone could talk about.

“Boston has seven daily newspapers at the time, and the Molasses Flood is so big for about a week that it knocks off the front page the Prohibition amendment which essentially passes the night of the Molasses Flood, and it knocks the Versailles peace talks, the talks that ended World War I, off the front page, so it’s an enormous story in Boston at the time,” described Puleo.

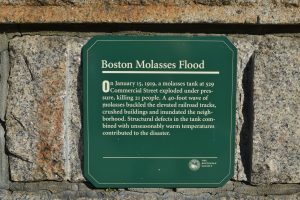

Boston politicians responded with outrage, but it didn’t last long. Puleo thinks that’s because of who was living in the North End, mostly Italian immigrants. They didn’t have the political power to stop industry from taking over their waterfront, or molasses from leaking onto the streets. And today, their story has been largely forgotten, aside from a plaque in the spot where the tank once stood.