Remembering Ann Taylor, free spirit, skier, missed connection

The sky glows over Burlington, VT, near the end of August. (Anna Van Dine / VPR)

A lot of the stories you hear on VPR start with observations. A sign pinned to the bulletin board at a general store might spur reporting, or an offhand comment from a public official at a meeting.

Sometimes, reporters hang onto things they’ve noticed, waiting for the right opportunity to pursue them. And sometimes, we wait too long.

It was after 8 p.m. on Aug. 26. The sun had gone down, and I was late meeting friends, but I just couldn’t stop watching Ann Taylor.

Listen to the audio version of this story at VPR.org.

It started about an hour before, when I sat on a bench at Perkins Pier in Burlington and pulled out my book. I’d hardly read a page when I first heard her voice. It was a bright voice, loud and friendly. She’d gone up to two women, who were standing at the edge of Lake Champlain, tossing flowers into the water.

Who was she? What was she doing? I held my book and pretended to read. But really, I was watching Taylor.

“You couldn’t go to a restaurant with her without her introducing herself to virtually everybody there,” said Lynette Reep, who became friends with Taylor in the early 80s. “Anywhere she went, she just — she wanted to meet everybody, she wanted to talk to everybody.”

Ann Denise Taylor was born on Sept. 14, 1951, in Manchester, New Hampshire. She graduated from the University of Vermont with a degree in physical therapy, and had a private practice in the area for decades.

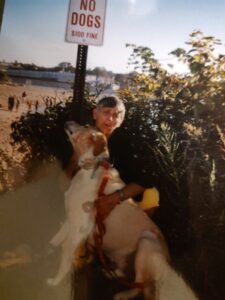

Ann Taylor displaying two of her passions: dogs and rule-breaking. For years, she had a dog named Bode Miller, after the ski racer. Her friends said her voicemail greeting went, “Hi, this is Taylor and Bode. Please leave a message.” (Courtesy Charles Woodbury)

She loved people, the mountains, and light on the water. More than anything, Taylor loved to ski. She was elegant in powder — heads would turn to watch her go down. She spent time in Utah, skiing at Snowbird with her friend Alice Colwell.

“She would know exactly where to go,” Colwell said. “She would invite people to come and ski with her. And [she would say], ‘I’ll show you where to go! I know this mountain! I’ll show you the hidden spots!’”

Taylor was fierce and free-spirited, always making connections, always trying to help people. Iginia Boccolandro was her partner throughout the 90s.

“She had a joie de vivre, you know, a joy for life and for everything that’s good in life,” Boccolandro said. “Looking at nature and good food and good drinks. And she would, you know, look at a fabric and touch it with her fingers. [She] was very kinesthetic, very gregarious, extremely outgoing, and often very self-centered as well.”

Taylor would be seized by burning passions — once, she chained herself to a giant cottonwood tree, to try and stop it from being cut down to make way for the Burlington bike path.

“I think she was quite proud of that little bit of civil disobedience there,” Lynette Reep said. “I’m not sure what it was about that particular tree that drew her attention, maybe just that its days were numbered.”

So were Taylor’s. She was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1992. Ten years later, it was in her bones. The treatments made them brittle, and they kept breaking. She was on crutches when I saw her on Perkins Pier, that evening back in August.

Eavesdropping that night, I heard the women tell her why they were throwing flowers into Lake Champlain. It was to honor someone who had just died. I heard Taylor tell them she lived in Shelburne, but liked Burlington better. I heard her talk about skiing. I heard her interrupt herself mid-sentence to say, “Oh my God, look at the lake.”

After the women left, Taylor marveled at the sight of a single cloud, behind all the others, that caught the sun and glowed. It looked radioactive, otherworldly.

Ann Taylor (right) and her friend Lynette Reep. In an email, Reep said this obituary felt as if Taylor herself were “reaching out from ‘beyond the veil’ as they say in old mystery novels, and tweaking her legacy.” (Courtesy Lynette Reep)

Then the sun went down, and Taylor began to walk back towards the city. I hesitated, then stopped her.

“Excuse me,” I said, “I make radio stories, and you seem really interesting, I wonder if maybe we could talk sometime?”

She was delighted, and gave me her phone number.

Taylor’s friend Alice Colwell said this was a fitting encounter.

“One of the other things that she used to do was that she would — in this last couple of years in particular — she would call up people that she had in her phone that she couldn’t remember how she knew them or why,” Colwell said. “And she would call them up and say, ‘I have your phone number. And I want to know who you are and how I know you.’ And she would talk to them.”

I thought about Taylor often after we met. But I kept waiting to call. The time just never felt right.

“The other thing she used to do,” Colwell said, “was that she wanted to go and interview all kinds of older people and get their stories because she felt they had so much to tell.”

But I waited too long. Ann Taylor died on Feb. 1. She was 70 years old.

Have questions, comments or tips? Send VPR a message or get in touch with reporter Anna Van Dine @annasvandine.