Racist covenants still stain property records. Mass. may try to have them removed

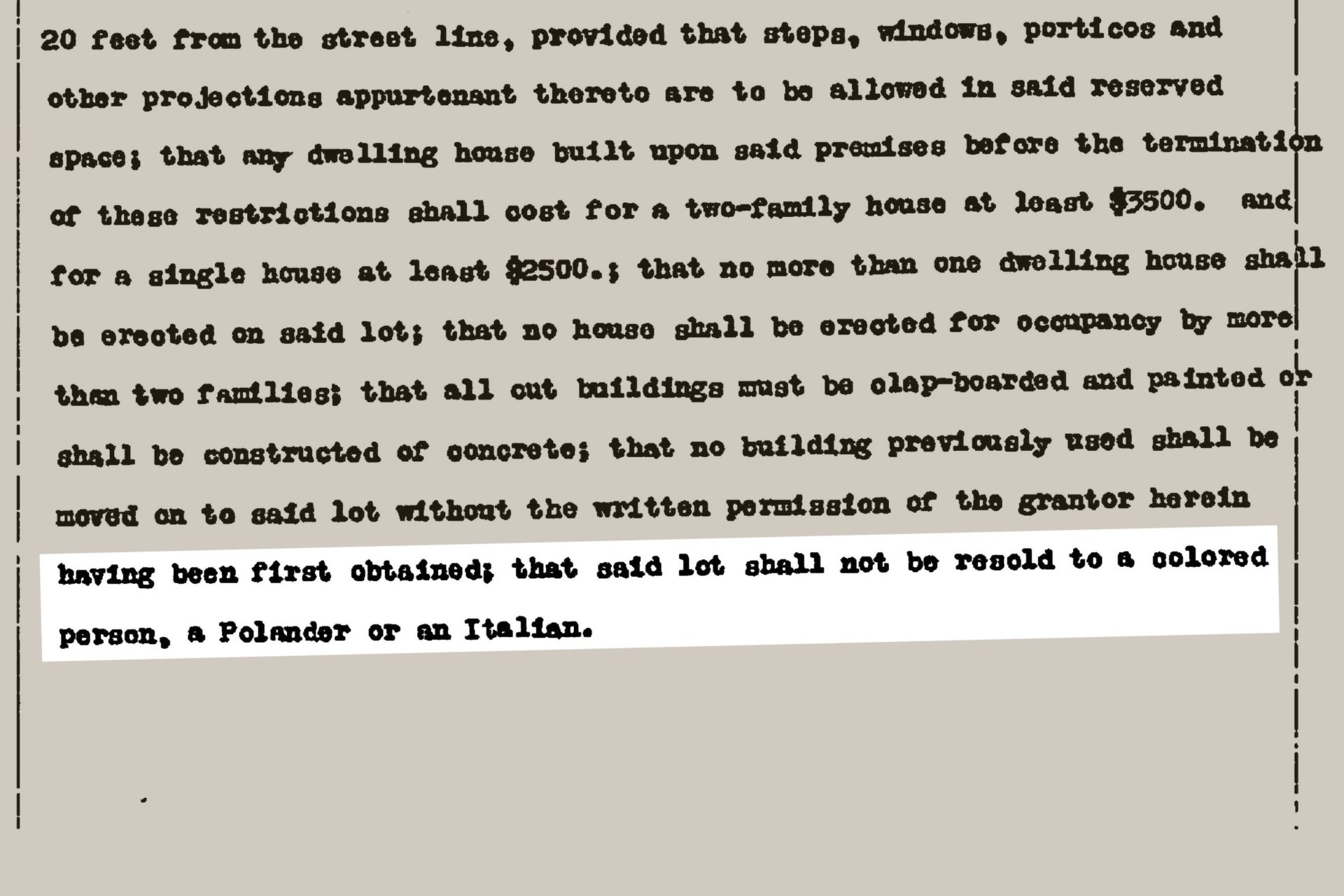

A deed from Springfield, Mass., in 1916 states that “sad lot shall not be resold to a colored person, a Polander or in Italian.” This language appears on the deeds for at least four separate properties in Hampton County. (Courtesy of Hampden County Registry of Deeds)

In the bedroom community of Wilmington, Mass., just south of Lowell, sits a little white house, with paint peeling from the trim and a mailbox emblazoned with the American flag at the end of the driveway.

Homeowners Edward Kaizer and his wife Mary Tassone-Kaizer say the house has been in the family for generations. But they were shocked when a WBUR reporter showed them a clause buried in their property records, from 1897, stating the land cannot be occupied by “negroes or Irish” or anyone considered “disorderly people.”

“Oh my God,” said Tassone-Kaizer, who works in accounts receivable for a local company. “Did your parents know about that?”

“If they did, they didn’t say so,” said Kaizer, a high school teacher in Wilmington who grew up in the house.

Kaizer held the document with a stunned look. Then he said his mother was an Irish immigrant.

“It’s disgusting,” Tassone-Kaizer replied. “We don’t stand for any of that.”

Racial Covenants

So-called racial covenants can be found in property records all over the country, including Massachusetts, where many restrictions were written from the late 19th to mid-20th century. Some bar landowners from selling or renting to people who aren’t white, others target certain immigrant groups — like Poles, Italians and Irish.

Experts note the racist clauses have had no legal standing for decades, thanks to court decisions and legislation that now makes racist deed restrictions illegal. In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial covenants were unenforceable. And in 1968, Congress outlawed them altogether as part of the Fair Housing Act.

The following year, Massachusetts also banned restrictions on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin and sex.

But some state lawmakers and judges remain concerned that the clauses are still included in property records, a reminder of the country’s — and the state’s — legacy of racism. And now they are trying to figure out the best way to correct the historical record.

The Massachusetts land court recently started letting judges add a note to deeds saying the covenants are void.

“It allows for a formal repudiation of the records,” said Lauren Reznick, an administrator with the state land court, “and it does so without erasing history.”

Some say that’s not good enough.

Read the rest of this story and hear the audio version at WBUR.org.