Episode 32: A Tall Order

This hour, we parse what’s clear, what’s changed, and what hasn’t about U.S. immigration policy and the powers of ICE, the federal immigration police. We hear what the vetting process was like for one refugee in Maine, and follow NPR’s Code Switch podcast as they trace Puerto Rican identity in a Massachusetts town. Plus, we take a look into the often-overlooked history of slavery and emancipation in New England.

President Trump’s executive orders on immigration have brought renewed focus on the role of individual ICE agents. Photo by Groupuscule via Wikimedia Commons

Who’s In, Who’s Out

President Donald Trump’s first executive order on immigration included a temporary ban on travel from seven majority-Muslim countries. It was challenged by many states, and was suspended after a legal battle.

Trump’s new order, signed Monday, is meant to achieve the same goals while passing legal muster. Lawyers in New England and elsewhere in the country have promised to fight this order in court, too. Reporter Shannon Dooling covers immigration for WBUR and the New England News Collaborative and joins us to help understand the new rules.

Trump has talked repeatedly about the need for “extreme vetting” of refugees and other immigrants coming from majority-Muslim countries. But what does that vetting process look like now? Maine Public Radio’s Fred Bever has the account of one refugee who came to Maine from Uganda last September.

A market at the Kyangwali refugee settlement in Uganda, where Maine resident and Congolese refugee, Charles spent almost half his life. The number of refugees, asylum seekers and other foreign-born people who settled in Maine last year was the largest in recent years. Photo by N. Omata via Flickr

The travel bans are a part of the administration’s overall immigration crackdown. In one executive order, entitled “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” the president wrote, “We cannot faithfully execute the immigration laws of the United States if we exempt classes or categories of removable aliens from potential enforcement” — a reference to Obama administration guidance to prioritize serious criminals for deportation.

Depending on how you read the guidance from Department of Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly, you could say that instead of broadening the priorities for deportation, the executive order essentially stripped away priorities altogether, making almost any non-citizen vulnerable for deportation. White House press secretary Sean Spicer has said that the president wants to “take the shackles off” immigration enforcement agents.

But as Shannon Dooling reports, individual ICE agents have always had a certain amount of discretion. The question now is how that discretion will play out under the new administration.

So Far, and Yet So Close to Home

The Holyoke Public Library collected family stories from Puerto Rican residents at an event last September. Photo by Katherine Davis-Young for NEPR

Last week marked the 100th anniversary of the Jones Act, which granted U.S. citizenship to people born in Puerto Rico. Today, there are more Puerto Ricans living on the mainland than on the island, which is in the midst of an economic crisis.

In the 1960s and ’70s, a large group of Puerto Ricans moved to Holyoke, Massachusetts, where they found work in factories and nearby tobacco fiends. Holyoke is now home to the highest per capita concentration of Puerto Ricans in the United States.

Reporter Shereen Marisol Meraji paid a visit to Holyoke for the NPR’s Code Switch podcast to explore what the Jones Act has meant for Puerto Ricans living in the 50 states.

Silvana Laramee works with her students at Alfred Lima Elementary School in Providence. Most of the city’s ELL student population is Latino, but in the last few years, the district has welcomed more than 200 refugee students from all over the world. Photo by Ryan Caron King for NENC

In Rhode Island, the population is about 14 percent Latino. And that population is growing, with Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Guatemalans, and Colombians the largest Hispanic groups there. But the number of teachers certified to teach English language learners hasn’t kept pace with the demand. Rhode Island Public Radio’s Ambar Espinoza reports.

Seeking Freedom

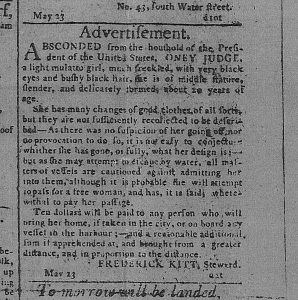

Ona Judge, a runaway slave of President George Washington, lived most of her on New Hampshire’s Seacoast after gaining her freedom. Seen here, a reward advertisement for her return. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Ona Judge, a runaway slave who evaded George Washington himself, lived most of her years on New Hampshire’s seacoast after gaining her freedom. New Hampshire Public Radio reporter Hanna McCarthy spoke with Erica Dunbar, author of the new book Never Caught: The Washington’s Relentless Pursuit of Their Runaway Slave, Ona Judge, along with others who are working to keep Judge’s history — and the history of the black community in Portsmouth – alive.

The first law in New Hampshire to be interpreted as outlawing slavery was passed in 1857, nine years after Judge’s death. Slavery was recognized by law across New England in the colonial period. After the Revolutionary War, emancipation was a gradual process.

Our guest Manisha Sinha, author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition, writes that enslaved people played a much larger role in that process than they’re usually given credit for; in many cases, suing for their freedom.

About NEXT

NEXT is produced at WNPR.

Host: John Dankosky

Producer: Andrea Muraskin

Executive Producer: Catie Talarski

Digital Content Manager/Editor: Heather Brandon

Contributors to this episode: Shannon Dooling, Fred Bever, Shereen Marisol Merjai, Ambar Espinoza, and Hannah McCarthy

Music: Todd Merrell, “New England” by Goodnight Blue Moon, “Tus Ojos” by Héctor Lavoe, “Soul Alphabet” by Colleen

Web help this week from Alexandra Oshinskie

We appreciate your feedback! Send praise, critique, suggestions, questions, story leads, and historical documents to next@wnpr.org.