Episode 16: Life’s Rich Demand

We have more choices for our Thanksgiving meal than the Pilgrims could have dreamed of. But did we make the right choice when we decided to breed traits like herbicide resistance into some of our most common crops? And should we have the right to know when we’re buying foods made with genetic engineering? We hear from both sides of the GMO debate.

Later, we visit an innovative policing program that changes the relationship between police and people with opioid addiction. Plus, a reporter interviews one (in)famous pilgrim, and a tribe welcomes visitors to a new cultural district on Martha’s Vineyard.

Sweet corn that you buy at the farm stand or supermarket in the summer is not genetically modified. But genetically engineered corn is used as an additive in processed foods and included in livestock feed. (Credit: United Soybean Board)

Engineered

Writer Caitlin Shetterly suffered for years with a series of puzzling symptoms: constant colds, tingling and numbness, rashes, and all-over pain and weakness. She tried every treatment she could find, with no relief. That’s until an allergist recommended she tried eliminating GMO corn from her diet.

She managed to do so, and her health improved.

That’s what set Shetterly off on a journey — interviewing farmers, scientists, and activists — that led to her recent book, Modified: GMOs and the Threat to Our Food, Our Land, Our Future.

That’s what set Shetterly off on a journey — interviewing farmers, scientists, and activists — that led to her recent book, Modified: GMOs and the Threat to Our Food, Our Land, Our Future.

It’s difficult for consumers to make informed decisions on the safety of GMOs, because most of the research is either carried out by or funded by companies like Monsanto, which manufacture the modified seeds, says Shetterly.

A report published this May from the National Academies of Sciences found GMO foods to be safe. However, the report recommended testing GMO crops for residue from glyphosate, the main ingredient in the herbicide Roundup (which is routinely sprayed on GMO crops, since they are bred to be immune to the weedkiller).

The WHO’s cancer agency last year classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic.” This year, though, the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation and a different WHO body declared glyphosate “unlikely to pose a carcinogenic risk to humans” through our food.

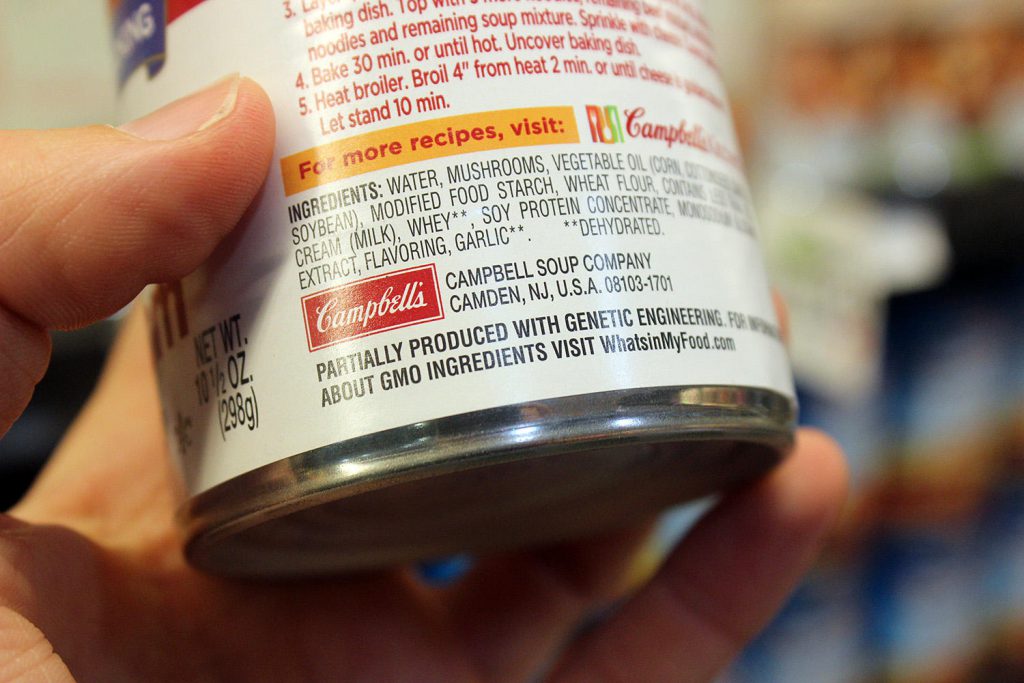

Campbell’s says it wants to be transparent about the GMO ingredients used in its foods, regardless of legal requirements. (Credit: Kathleen Masterson/ VPR)

With all of this confusing information, you might want to play it safe by avoiding genetically modified ingredients. Vermont, Connecticut, and Maine all have GMO labeling laws on the books. But federal legislation signed by President Barack Obama in July nullified the state laws. And advocates complain the federal law does not go far enough.

To break down the politics and economics of the GMO debate, Vermont Public Radio reporter Kathleen Masterson joins us.

Something Totally Different

John Rosenthal, left, co-founded the Police Assisted Addiction Recovery program in Gloucester, Mass. Steve Lesnikoski, right, was his first client. (Credit: Kristin Gourlay/ RIPR)

“You have to be in this absolute desperate state and just devoid of humanity to really change. And that’s where I was. I was dead inside. And I saw this beacon of light all the way across the country, and I was like, why not?”

– Steve Lesnikoski, former heroin user

The opioid addiction crisis in New England has physicians, community care-givers, and addiction treatment professionals scrambling to respond.

Police departments are responding as well. Many have added the overdose rescue drug, Narcan, to their tool belts. Others have stepped up efforts to prosecute heroin dealers.

But in Gloucester, Massachusetts, there’s a program that flips policing on its head to help addicts find treatment. Rhode Island Public Radio’s Kristin Gourlay has the story. Find more of her reporting on RIPR’s health blog, The Pulse.

Legacies

Tourists walk through the Shops at Aquinnah, part of the newly established Aquinnah Cultural District on Martha’s Vineyard. (Credit: Andrea Shea/WBUR)

Aquinnah Wampanoag tribal member Berta Welch is owner of the Stony Creek Gift Shop in Aquinnah, on Martha’s Vineyard. The shop originally opened 75 years ago. (Credit: Andrea Shea/ WBUR)

Even though the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe has lived on Martha’s Vineyard for more than 10,000 years, tourists who flock to the island don’t always know about or get to experience the rich history.

But now people from the tribe and the town of Aquinnah are working together to tell that story — and to boost the local economy — with a new, state-designated cultural district.

WBUR reporter Andrea Shea takes us there. Find a text version of Andrea’s report along with photos at WBUR’s ARTery.

Buddy Tripp, a Myles Standish reenactor at Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Mass. “I am afraid of nothing but God,” Tripp tells reporter Annie Sinsabaugh, in character. (Credit: Annie Sinsabaugh/ Transom Story Workshop)

Whether it’s civil war generals depicted in town square statues in the South, or the controversy over Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill, Americans are grappling with the complicated history of iconic figures.

The Myles Standish Monument in Duxbury, Mass. (Credit: Scott Christy)

New England is no exception. At Yale University, students have protested a dorm named after John C. Calhoun, a former U.S. Senator, Vice President, and supporter of slavery. In the state of Vermont and the city of Cambridge, Massachusetts, Columbus Day is now Indigenous People’s Day.

Reporter Annie Sinsabaugh wonders if the same scrutiny should be applied to a man seen as a hero to the pilgrims: Myles Standish. Her story was reported as part of the Transom Story Workshop.

About NEXT

NEXT is produced at WNPR.

Host: John Dankosky

Producer: Andrea Muraskin

Executive Producer: Catie Talarski

Digital Content Manager/Editor: Heather Brandon

Contributors to this episode: Kathleen Masterson, Kristin Gourlay, Andrea Shea, Annie Sinsabaugh

Music: Todd Merrell, “New England” by Goodnight Blue Moon, “Mr. Farmer” by the Seeds

We appreciate your feedback! Send praise, critique, suggestions, questions, story leads to next@wnpr.org, and tell us what you’re thankful for.