Bringing Hydro Power From Canada To Massachusetts: Comparing Northern Pass And New England Clean Energy Connect

We’re going to take you on a journey. It starts in frigid Québec, where a gigantic, decades-old project that dammed rivers and forced native people off their land and has become a source of provincial pride, and a lot of power.

Power-hungry Massachusetts saw Hydro-Québec’s big dams as a zero-carbon answer to their prayers. The state solicited bids for all kinds of projects to bring 1,200 megawatts of renewable energy to the Commonwealth. And in January of 2018, the state announced it had picked the Northern Pass transmission line–a project of giant utility Eversource–to deliver a big chunk of that power in through New Hampshire. Northern Pass was controversial from the start, and only a week after the announcement, New Hampshire’s site evaluation committee denied the final permit for the project.

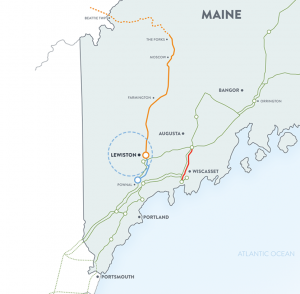

Massachusetts then went to Plan B which is creating a different transmission line from Québec that cuts through the state of Maine: Central Maine Power’s New England Energy Connect. Now, a year later, this project while also controversial, is getting more and more support, including from Maine Governor Janet Mills.

So what about these two projects led to such different outcomes? And what does it mean for the energy mix for our entire region?

We called up two reporters who have been covering these issues closely: New Hampshire Public Radio’s Annie Ropeik and Maine Public’s Fred Bever.

For more on Hydro-Québec go listen to Outside/In‘s “Powerline” Series. And, for an in-depth look at the project through Maine, check-out Fred Bever’s series, “Power Struggle in the Maine Woods.”

Interview Highlights

These interview highlights have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

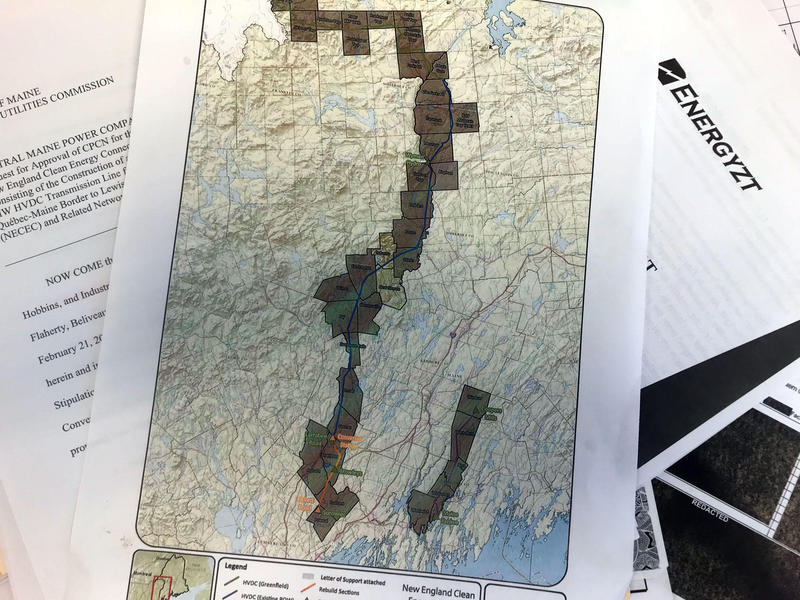

The current proposed Northern Pass route would bury the line in the White Mountains as a concession to opponents. Photo courtesy of Northern Pass

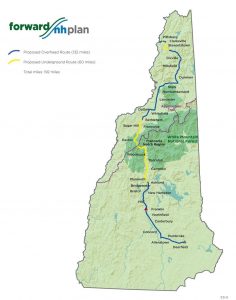

Annie Ropeik: This is a 192-mile transmission line, those are the tall towers the kind of the biggest scale power line you see. It would have been partly buried, gone down through the White Mountains of New Hampshire from Canada, and then emerged into central New Hampshire where the power would have been distributed down into southern New England. It had a price tag of $1.6 billion, and I should note that the Northern Pass project also predated that Massachusetts state law as well. It was just sort of a bonus for them as they had a new funding opportunity that if this project, which was already in the works got picked by Massachusetts it would help them recoup some of its costs more quickly. All they had to do was get their final building permit from the state of New Hampshire.

John Dankosky: So you’ve got this huge utility that wants to sell power to Massachusetts residents. You’ve got the support of Massachusetts state government, but then it fell through. What happened?

Ropeik: Yes, so it was quite dramatic. I mean the Massachusetts decision where they pick Northern Pass came out January 25th and then by, I think, February 1st the state Site Evaluation Committee which is this board of different State Departments and representatives of different stakeholder groups which is in charge of approving big energy projects, they denied Northern Pass on around February 1st. They’d only been in deliberations for a few days and again this came after literally years of hearings leading up to these deliberations. They had scheduled a few weeks of deliberations. So it was a huge surprise when I think on day three they said, we don’t believe this project can pass muster we’re ready to vote it down right now. And they did.

And so basically the Site Evaluation Committee has some criteria that are laid out in our state law that they are judging all of these projects against. Whether it’s, you know, a relatively small solar project that just makes the cut of being considered large scale or something really enormous and transformative like Northern Pass. The projects had to be financially sound. They had agreed that Northern Pass was, and then they have to meet this other sort of tests of their impact. So they can’t have too big of an effect on the environment or tourism or aesthetics along their route.

They must be found to be in the service of the public good which is this kind of subjective criterion and then the last one is that they cannot upset orderly development in the region. And that was the one ultimately that sunk Northern Pass that was the one that site evaluators decided that there was no way that they were going to find that the project could meet that test and so they didn’t even talk about the other two and they voted unanimously to reject the project which has now set off this ongoing appeals process that we’re still in the middle of right now.

So we’ll get back to Northern Pass in a moment, but Fred I’ll turn to you. Once Northern Pass falls apart, this is an opportunity for the CMP project that would go through Maine to be resuscitated. So, tell us about that. What was the process by which Massachusetts decided to go with CMP as Plan B?

Fred Bever: Well, Massachusetts basically took a new look at all of the bids it had, and one and done was clearly something that the Massachusetts regulators were interested in. And CMP was that kind of project and it was about $600 million cheaper for Massachusetts than the Northern Pass project. So, the cost, I think, was the big deal. CMP had been laying the groundwork for getting its permits. It was pretty canny about that, it’s done this kind of project before and it’s, unlike the other bidders, really transmission focused.

So the big factor is cost obviously, they’d done some of the groundwork in advance something that maybe Northern Pass hadn’t done. Maybe you can describe the project itself Fred, if Northern Pass was going to cut through the White Mountains and other sensitive environmental areas and that’s one of the concerns people had. What does it look like coming through Maine?

Bever: So the entire corridor is about 141 miles from the Canadian border down to Lewiston, Maine where there’s a big interconnection into the regional grid and most of that requires upgrades: taller towers, more robust lines for the high voltage DC current that would be coming from Canada into the regional grid. But the most controversial part is about 53 miles of new corridor going through the forested territory in western Maine and its mountains across some of its rivers. And that’s been where a lot of the controversy has focused on whether the trade-off between cutting through the woods there is worth it compared to whatever Maine’s going to get out of this project.

One of the problems that dogged Northern Pass was that it didn’t have some of the necessary permits in place. And as it got started it led to perhaps its demise. What did Maine have already in place to allow this project to get started more quickly?

Bever: Well one thing is that while it’s still in the permitting process now and always needed certain permits, Central Maine Power had secured the entire corridor that it needed. Of course, [they] already had the existing parts of the corridor, but it had also secured either ownership or easements across a particular route. They had also started negotiating with various towns which would get some property tax benefit out of the project to get their support for the project from their local governments. And, in addition, none of this is on public lands, because a good deal of the Northern Pass project was actually on national forest land so there isn’t the same sort of public resource and public interaction that there was at Northern Pass.

Ropeik: Yeah, that’s true. I mean Northern Pass had to go through a number of really high profile court battles to try to secure some of the land that they needed so they had all their land lined up but it hadn’t been automatically available to them. They had to negotiate with a lot of environmental groups for the national forest to get some of the corridors that they needed but the rest of it was an existing rights of way and that’s something they really pushed a lot. They still had some of those little details to be worked out or not so small details depending on who you ask, whereas Northern Pass, one thing that got them in trouble is they may have treated that Site Evaluation Committee approval not as a given, but as, we’ve made it this far. We can make it over this hump.

A key part of any project like this, if you’re going to take a power line through one state ostensibly to get power to customers in a completely different state is the residents of that state New Hampshire or Maine, probably have to get something out of it. What were New Hampshire residents told they’ll get if Northern Pass cuts through the White Mountains and goes all the way down to Massachusetts?

Ropeik: One thing they were told is that they were not going to have to foot the bill for this alone. New Hampshire-ites were not going to have to worry about paying to bring power to Massachusetts, in theory. There also were certain economic development funds that were going to be made available as part of the project. Eversource was calling one of those the Forward New Hampshire Fund which was for $200 million and a lot of that was going to support economic development in the more depressed rural parts of our north country around the White Mountain. Some of those towns that have suffered from the closure of certain paper mills and forestry sectors and they rely a lot on ski tourism and in White Mountains revenues. Then they also were going to make some upgrades to utility infrastructure in the North Country to again help bring better service and economic opportunities to these towns. But there were not, in my view, and Fred you can correct me here, it doesn’t seem like there were large scale statewide incentives besides doling out millions of dollars in economic development funds, but CMP has quite a bit more of a range of incentives, is my impression, and I think that’s something that sets the two apart.

Bever: One really important difference between the incentives package is that Central Maine power didn’t offer a package at first. Nothing at all. Nothing above and beyond the project itself and the purported benefits that that would bring. So that was one reason CMP could make its offer to Massachusetts at $600 million less than Northern Pass was, that it didn’t have to dole out benefits. But they did early on make a guarantee that businesses and residents would never be on the hook for any of the costs of building this new transmission line. In addition, it would enjoy the benefits of lower energy prices throughout New England because of this pulse of clean energy basically subsidized by Massachusetts residents. After then-candidate for governor, Janet Mills said I’m not so sure about this project. This is during the campaign, I don’t think I could support it as it is now, I really want them to bring some more to the table. That’s paraphrase but that’s the message she sent.

So then Annie what happens next with that project as you say, it predates this request for power from Massachusetts. All of New England, these states are growing they need more energy and they’re going to want more than maybe just 10 percent of their energy to be renewable or coming from hydro-sources. Is there still life left in a Northern Pass project?

Ropeik: It really remains to be seen. You know we’re waiting to see what the Supreme Court does with it. They may issue kind of a narrow ruling that’s really more about the SEC’s process than about whether Northern Pass is a good project or not. I actually think that’s somewhat likely, it’s not really the Supreme Court’s job to approve this project, they’re looking more at whether this violated SEC rules or whether SEC rules need to be clarified in some way to prevent this kind of chaos in the future. But you know one potential outcome is that the Supreme Court says yes according to the letter of the Site Evaluation Committee law you didn’t do your due diligence and you need to do it again you need to reconsider the project and do it in this correct way and that could potentially lead to a different outcome for Northern Pass. Eversource is certainly acting as though Northern Pass still has life left in it and in fact when I talked shortly after Massachusetts dumped the project to former Eversource spokesman, Martin Murray, you know he was intimating that Massachusetts was not you know the only player in the game.

So I think that Eversource would like to develop Northern Pass whether or not they have an obvious immediate single customer to buy the power like Massachusetts would have been. This is a capital project. I mean Eversource can do this if they can get the approvals for it they don’t need a specific buyer and they can just sell the power straight into the regional grid and pass the costs on to ratepayers potentially, or you know do it through some other means and so I think it’ll be really interesting to see what comes out of the state Supreme Court and I think Eversource is going to do all they can to try to revive this project in some way although I think that there probably are not so many options for them to do that but they’re going to do what they can for sure because they’ve invested millions of dollars into this campaign so far so they’re not going to let it go easy.

Bever: I think they would mind if the CMP project here in Maine went away.

Ropeik: Oh sure yeah. I mean can you imagine if they switched back to Northern Pass?

Bever: I’d rather not. One thing I do want to mention in all of this we have been talking about Central Maine Power. We’re really talking about international energy giant Iberdrola which in turn owns Avangrid which in turn owns Central Main Power. And so this is like one component of a big playing field for moving to a more renewable energy future. Iberdrola is mainly in the wind energy business in Spain and so these big transmission projects these are all a part of what will be likely more demand for this kind of energy and for big transmission lines to do it. That’s one reason why some environmental groups here in Maine are taking a very careful look at the environmental permitting process and trying to say okay this could be a precedent. I think that that’s one important thing about watching this process in Maine is to see what the environmental regulators come up with in terms of mitigation for the ecosystem values that will be lost if this project goes through 53 miles of what right now is contiguous forest land.

This is an edited interview from the March 14, 2019 episode of NEXT. You can listen to the entire show right now. Find out when NEXT airs throughout all of New England.