The Surprising History Of New England’s Pirates

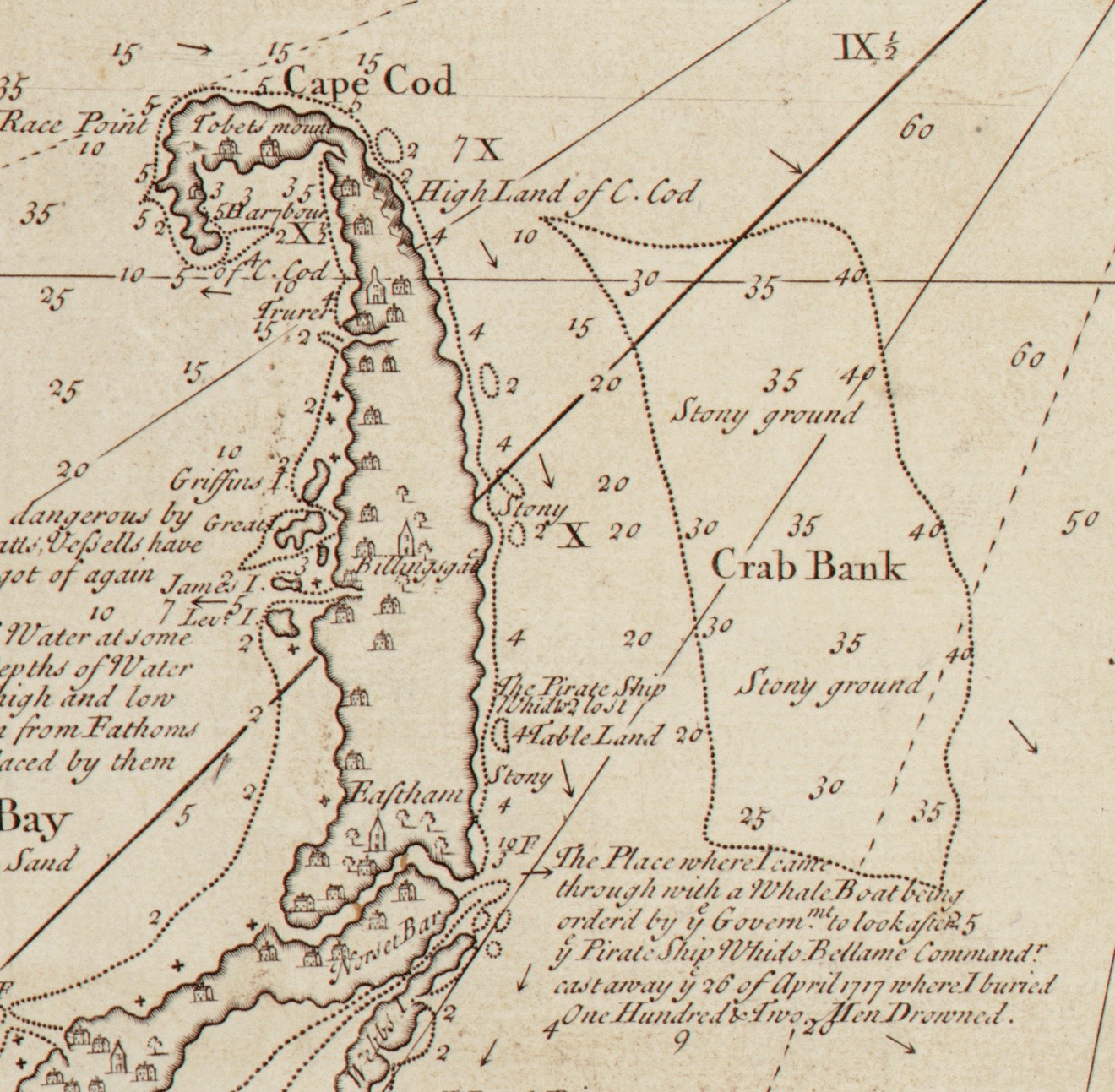

Detail of Cyprian Southack’s map of Massachusetts, circa 1734. A thick arrow (not original to the map) points to where Southack wrote “The Pirate Ship Whidah Lost.” Below that to the right is more text in which Southack informs the reader that he buried 102 men from the wreck who had drowned. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

When you think of pirates you probably think of the skull and crossbones, wooden legs, parrots, eye patches, and marauders swashbuckling their way through the Caribbean.

When you think of pirates you probably think of the skull and crossbones, wooden legs, parrots, eye patches, and marauders swashbuckling their way through the Caribbean.

But New England, or the New England colonies to be specific, actually played an important role in the “Golden Age” of piracy, a period that spanned the late 1600’s through the early 1700’s.

That’s the subject of Eric Jay Dolin’s new book, Black Flags, Blue Waters: The Epic History of America’s Most Notorious Pirates. He joined us to describe the relationship between pirates and the New England colonies, but he began by telling us some of the remarkable story of Sam Bellamy and the ship, the Whydah.

Interview Highlights

These interview highlights have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

John Dankosky: What can you tell us about the story of the Whydah?

One of a series of “Pirates of the Spanish Main” cards that the Allen & Ginter Company produced circa 1888, and inserted into their cigarette packs. This one shows Samuel Bellamy and a scene of the wreck of the Whydah, both imagined by the illustrator. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick

Eric Jay Dolin: Sam Bellamy and Paulgrave Williams, two pirates that began their lives coming out of New England, headed down to dive on Spanish treasure ships. They failed to get much money that way, so they veered into piracy, and they plundered about 50 ships. But that was nothing compared to when they overtook the Whydah. The Whydah had just sold 500 slaves in Port Royal on Jamaica, so they were loaded with silver and gold, so when Bellamy and Williams took over the Whydah, they suddenly had a jackpot. They headed north but they wouldn’t be able to share the spoils of their success because in April of 1717, while they were sailing around the outstretched arm of Cape Cod, a Nor’easter blew down the coast, smashed into the ship, sank the Whydah. 161 pirates on board died, and all of the treasure sank to the bottom and stayed there for about 260 some odd years until a salvager and diver named Barry Clifford and his men actually discovered the location of the Whydah, only about 1,000 or 1,500 feet off the coast of Wellfleet on Cape Cod.

They started recovering the treasure. They even recovered the bell that said the “Whydah Gally” so they knew they had this treasure, and this is significant because it’s the first authenticated pirate ship and treasure ever found. And they’ve been recovering treasure ever since. How much the treasure is worth is a matter of debate, an unreasonably low estimate is about $200,000, an improbably high estimate is about $400 million. But if you’re ever on the Cape in West Yarmouth there’s the Whydah Pirate Museum which does a wonderful job telling the story of the Whydah and how the treasure has been recovered.

Allen & Ginter cigarette card insert, circa 1888, showing Edward Low and a scene of him “torturing a Yankee,” both imagined by the illustrator. Other than one contemporary source that said Low was a small man, we know nothing about how he looked. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Jefferson R. Burdick Collection, Gift of Jefferson R. Burdick

Tell us the story of Philip Ashton.

Philip Ashton, from my hometown of Marblehead, Massachusetts. He was a fisherman off of Nova Scotia, in the summer of 1722 when a notorious, despicable, likely deranged pirate named Edward Low, captured his fishing vessel and other fishing vessels and forced Ashton among others to become pirates, but Ashton was able to escape from the pirates clutches in the Bay of Honduras, and he landed on Roatán Island, which was an uninhabited island, and he lasted there for almost two years, most of it entirely alone, until a brigantine from Salem, Massachusetts, right next to Marblehead, picked him up, brought him back to Marblehead. When he walked in the front door of his parents house, they thought that he had risen from the dead because they had long assumed he was gone forever, and his story was a huge story in New England because Daniel Defoe had written a famous book in 1719 called Robinson Crusoe, well here it was in 1726 when Ashton comes back from the dead and he was a real-life Robinson Crusoe and the Americans could claim him.

Who were these pirates and why did they turn to this life?

The pirates I talk about, were generally of English descent, from the American colonies, there were other countries represented as well, and there were any number of reasons why they turned to piracy. All of them at root had one common goal: and that was to get rich. There were tales of pirates in olden days, before the 1600’s and 1700’s that I talk about, that had attacked ships and gained considerable treasure, and other pirates sought to emulate them by becoming pirates themselves. There were many ways in which people would turn to piracy. One was after a war had concluded, all of the privateers and naval men who had been engaged in the war, many of them found themselves suddenly unemployed. Especially the privateers who had the skills of a pirate, many of them just transferred almost seamlessly into piracy. Also, many sailors who found their captains to be particularly abusive or dictatorial would often rise up in mutiny, and once they had taken over the ship they would turn to piracy as well.

Another lure to piracy was the sinking of treasure fleets off of the Florida coast. People went down there to dive on the treasure fleets to try to recover the treasure, some were successful, some weren’t. But either way many of them, once in the Caribbean, decided to try their hands at piracy. But pirates were very much like gamblers going into a casino. People always have an over-expectation of success and an under-expectation of failure. And most pirates failed to achieve any great riches at all, and many of them died after a relatively short career. But the hope of plundering a valuable treasure ship was enough to get many men to throw their lot in with their fellow pirates and go to sea to rob whatever ships they could.

The front of a Two Escudos coin, or doubloon, minted in Seville, Spain between 1556 and 1598. Sold at auction in 2010 for $1,770. Courtesy Stack’s Bowers Galleries

So let’s go back to the 1600’s and early American colonies. Could you talk about the support that many colonists had for pirates?

In the late 1600’s there were these pirates called the Red Sea Men, which replaced the Buccaneers of earlier days, and these men would come from the colonies and they would travel in their ships around the Cape of Good Hope into the Indian Ocean, where they would attack Mughal Shipping that was transiting between India and the Red Sea ports of Jeddah and Mocha.

Many of these pirates came from the colonies, they were the fathers, the sons, the brothers of other colonists. And they brought back valuable and much-needed treasure to the colonies, and the colonies welcomed them back, because it was not viewed as being particularly bad to go halfway around the world and attack “heathens” and “infidels,” rob them of their treasure and bring it back to the colonies, which were traditionally starved of currency by the mother country and often forced to buy goods with currency. So here was this ready source of money that was being brought back to the colonies, by colonists, so they were truly welcomed with open arms.

And pirates needed the colonists to help too.

Pirates, like anybody else, need to have supplies, they need to careen their ships and scrape all of the foul matter off of the bottom of their ships, and they needed a support system. So the colonies in the late 1600’s provided the pirates with an extremely valuable support system, much like the Bahamas served in the 1700’s as a place for the pirates to repair to, repair their ships, re-provision, divvy up the loot, colonies were the pirates home base in the late 1600’s.

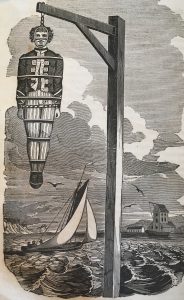

Captain William Kidd hung in an iron cage at Tilbury Point (1837 engraving). By Charles Ellms from The Pirates Own Book, or Authentic Narratives of the Lives, Exploits, and Executions of the Most Celebrated Sea Robbers. Courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Were there hotbeds of piracy in the New England colonies, places where pirates would hang out and be part of the population?

Yes, but you have to look at the distinction between the 1600’s and the 1700’s. In the late 1600’s, Newport, Boston were definitely places where pirates [visited]. In 1684 the Governor of Jamaica noted that Boston was a place where pirates had brought more than 80,000 pounds sterling into the town, and many of them had settled there, and it was considered to be a receptacle of pirates of all nations. Newport as well was known to be a pirate haven during the late 1600’s. But what happened after the War of Spanish Succession, even though piracy exploded, at this time pirates were no longer attacking Indians or Mughal ships half-way around the world, they were attacking English merchant vessels, many of which were issuing from the colonies.

So all of the sudden, whereas before, the colonists viewed pirates in a favorable light so they were benefiting from the pirates, now those pirates were attacking colonial ships, so that encouraged the colonists to come out against pirates, and as a result, the pirates had no places within the colonies, in New England or further to the South, to come in and re-provision and spend their money at grog shops. They were considered persona non grata, and they were forced to go down to the Bahamas. And then finally in 1718 when the Bahamas were re-taken by the British Navy, they were literally and figuratively at sea, fighting for themselves, getting more desperate all the time as the government clamped down on them.

An Excerpt From Black Flags, Blue Water

This is an edited interview from the November 8, 2018 episode of NEXT. You can listen to the entire show right now. Find out when NEXT airs throughout all of New England.