More Vermonters are carrying, and counting, amphibians at road crossings during spring migration

On a foggy, wet evening at the end of March, more than 50 people gathered on a dirt road in Salisbury, Vt., with flashlights and rain gear. Everyone was there for the same thing.

“I am here to help the salamanders,” said Rory Cate, a 10-year-old from Salisbury, who came with her dad and younger brother.

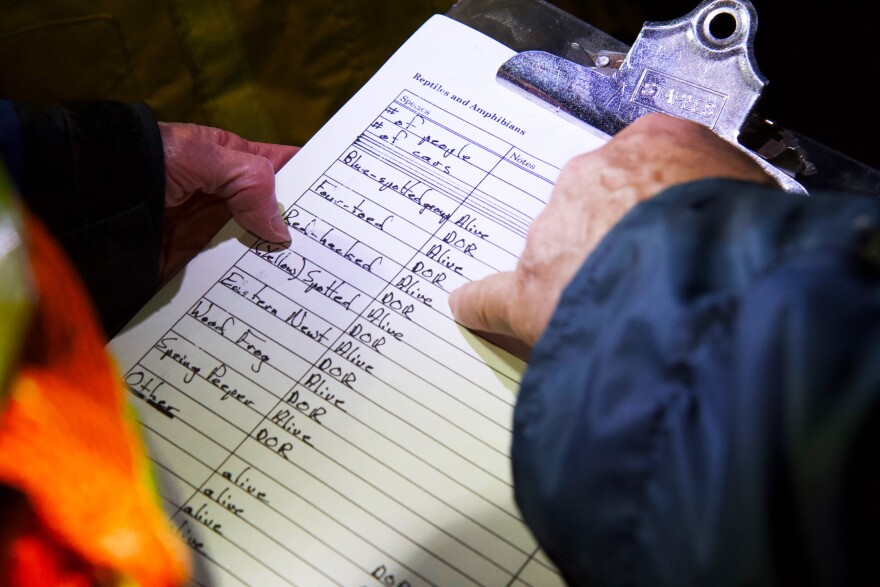

The idea is to scoop up frogs and salamanders from the road so they don’t get squished by oncoming cars. At the same time, volunteers walk around with clipboards to tally the number of animals and species.

Lots of people come out to see creatures they can’t find any other time of year — salamanders with bright yellow polka dots the size of a snickers bar, others with light blue flecks, and smaller ones with rusty red backs, alongside frogs you can hear singing into the summer months.

Wood frogs have adapted to freeze solid over the winter, except for the inside of their cells. For months, their heart stops and they no longer breathe. (Elodie Reed/ VPR)

These animals spend the winter underground, burrowed beneath the frost line or frozen solid, without so much as a heartbeat. Then, over the same couple of nights, they all move to ponds and swampy areas to breed.

“It’s not on your radar, but then when you hear about it you just go, ‘Wow, this is very cool,’” said Gary Sarachan, from Salisbury.

Others have deeper motivations. “I’m frightened of what we’re doing to the planet, and I can’t do much,” said Lyn DuMoulin, from Middlebury, Vt. “It’s just me. I’m almost 80 years old. So this is what I’m going to do.”

The data collection sheet for volunteers at the Salisbury amphibian crossing site, organized by the Otter Creek Audubon Society and the Salisbury Conservation Commission. Some volunteers have been coming to the site for over a decade. (Elodie Reed/VPR)

Venturing out at night in the rain to find these creatures was not always so popular.

“It’s a lot more mainstream now,” says Chris Slesar, who works on habitat connectivity with the Vermont Agency of Transportation. “It’s not like a fringe issue.”

And more people are going to new places during these migration nights, checking roads for crossing salamanders and frogs.

That’s according to the North Branch Nature Center in Montpelier. Last year, they had more than 500 volunteers submit surveys about amphibian road crossings — more than ever before.

One of those people was Ben Fletcher. He lives in White River Junction, and he started noticing the animals crossing his street a few years ago.

“The fact that they were completely just out in front of my home, that made it emotionally salient for me,” he said. “I did not have to walk far to see, well, the roadkill each morning and the frog and salamanders just hopping and being silly in the rain.”

Fletcher started a group called the Hartford Salamander Team in the early days of the pandemic to figure out where else roadkill is happening and try to prevent it.

His concern is not just sentimental.

“It does not take a lot of cars to do a lot of damage when you have hundreds of amphibians on the road in the span of just three or four hours,” said Brett Thelen. She’s the science director at the Harris Center for Conservation Education in Hancock, New Hampshire.

Several studies back this up — like one in Massachusetts looking at spotted salamanders. They’ve got goofy smiles and big yellow dots. It predicted that if about 10% of animals are killed by cars each year, that’s enough to wipe out a local population.

Thelen thinks about this constantly. She coordinates hundreds of volunteers at salamander crossings all over southern New Hampshire. But she knows shepherding the creatures across roads can only go so far.

“We can’t carry every frog across every road,” she said. “That is not a permanent solution to the road mortality issue.”

Rory Cate, 10, and her brother Thatcher, 8, help a spotted salamander cross the road in Salisbury. It was their first year at the site. (Elodie Reed/VPR)

Volunteers learn how to identify a red-backed salamander in Salisbury on March 31. Seven species of amphibians and one reptile were found on the road that night. (Elodie Reed/VPR)

Four years ago, Thelen helped convince the city of Keene to close part of a road that’s a hotspot for amphibian crossings. She says the city is the only place in New Hampshire that does this. The road is closed a few nights each spring, when conditions are ripe for a big migration.

“I’m the one who makes that decision, and then works with the city to close the road,” Thelen said.

But when she first suggested the idea of road closures at a city council meeting in the early 2000s, city officials weren’t too keen.

“They were very polite, and they smiled, and they nodded, and they said, ‘Thanks for your time, and we don’t think so.’”

Ten years later, she tried again. Only this time, volunteers came too. “It was standing room only and they all showed up in their reflective vests,” she said. “It was a completely different experience.”

After that meeting, the city council voted unanimously to close the road. They added a second closure this year.

Sarah Smith was inspired to create a comic about spotted salamander migration after seeing the creatures on a road near her home in White River Junction, Vt. She says they look like they’re wearing pajamas. (Lexi Krupp/VPR)

Groups like the one in Hartford, Vt., are hoping to replicate this success. In other places though, road closures aren’t an option. Like at a busy highway in Monkton, where over a thousand animals can move through on a single night — including a few rare species. Cars go fast and there’s no easy detour.

So back in 2010, the town’s conservation commission came up with another idea: To build two tunnels beneath the road for crossing wildlife.

They applied for a $150,000 federal grant, and got it. It was a big deal.

“This project gets talked about at conferences all over,” said Slesar, from the Agency of Transportation. “The work we did is often held up as the gold standard for how to do an amphibian crossing.”

Slesar helped coordinate the project, and he said it was only possible because of the information collected over decades by volunteers.

“That was the critical component to be able to justify getting those grants,” he said.

Construction finished in 2016. And since then, the state has recorded thousands of frogs and salamanders using the tunnel, alongside bobcats, mink and porcupines.

More projects like this might soon be possible. This past year, the federal government set aside $350 million to fund wildlife crossing infrastructure.

The state of Vermont is investing in this, too. This summer, the Agency of Transportation will finish a study mapping potential amphibian migration hotspots. Scientists are certain more of these major crossings exist that we just don’t know about yet.

Not every site will warrant a road closure or a big construction project. But it will be up to volunteers to go out at night, in the rain, and see what’s crawling or hopping across the road.