Lobstermen gather in Massachusetts to trade tales, confront an uncertain future

Lobsterman Dave Casoni, right, finds himself in an increasingly tense conversation with André Martinie, left, an entrepreneur who flew to the Cape from France to talk to fisherman about the “whale-safe” product he’s developed. (Eve Zuckoff / CAI)

Lobstermen spend most of their professional lives on the water in a solitary pursuit, but once a year, hundreds from the North Shore to the Outer Cape gather to talk shop and to wrestle with the challenges of an uncertain future.

The setting for the Massachusetts Lobstermen Association’s (MLA) annual weekend and trade show — a windowless conference room in Hyannis — almost couldn’t be further from a lobsterman’s typical environment.

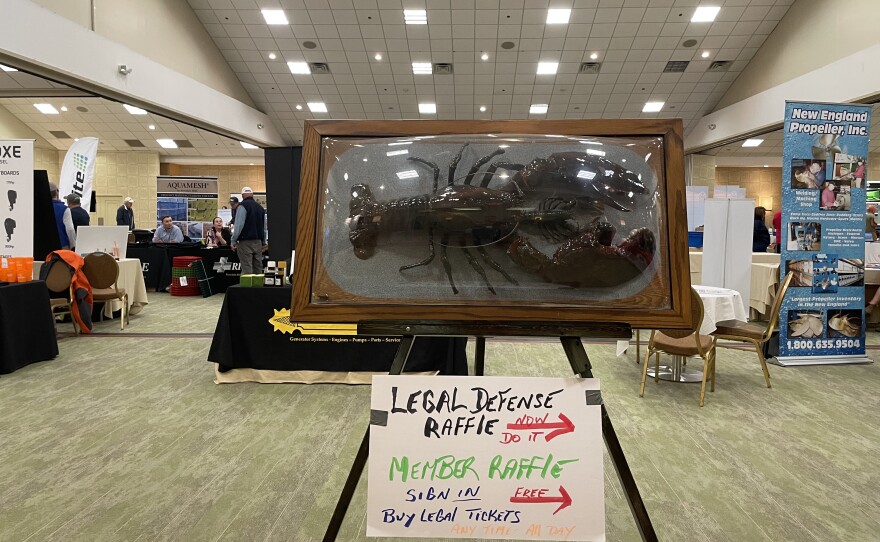

At the event last weekend, there was no sign that peaceful seas even exist, as lobstermen and their families moved from booth to booth. The 50 or so booths were staffed by fisheries regulators, and by vendors selling everything from nautical jewelry to boat motor parts to onboard pressure washers.

“The vendors here always have something that’s different, new,” explained Dave Casoni, a commercial lobsterman who serves as secretary and treasurer of the MLA. The chance to check out new gear is one of the main reasons the MLA has hosted this event for some 45 years, according to the MLA’s executive director. The other two reasons are to help lobstermen gain knowledge from experts, and to socialize.

“We want to get together and talk and complain with the other fishermen about everything,” Casoni joked.

In a small room down a hallway, lobstermen split off to attend information sessions led by scientists and officials who talked about sleep and stress at sea, controversial ropeless fishing gear, alternative bait, and more. Some sessions were standing room only.

“Today’s industry is paying much more attention to all of these facts than ever before,” Casoni said.

The fishery is in a moment of change. Lobstermen today are facing warming waters that are affecting lobster populations, offshore wind developers encroaching on fishing grounds, and strict fishing regulations imposed to protect critically endangered right whales.

(Eve Zuckoff / CAI)

And the conference room contained people who represent all sides of the conflicts.

“My name is André Martinie — and not ‘on the rocks,’” the CEO of Ecoseastem introduced himself, jokingly. Ecoseastem is a marine technology company. Martinie flew to the Cape from France to sell lobstermen on a product that he believes could protect North Atlantic right whales from entanglements in lobster fishing gear. There are an estimated 340 right whales left on the planet, and a number of deaths and injuries have been blamed on lobstermen’s gear, pushing federal and state officials to limit where, when, and how lobstermen can set their traps.

Martinie is introducing a product that he said would cut the line if a whale got entangled, allowing it to swim away without heavy traps dragging behind it.

But as he explained the product to Casoni, his challenge became clear: it’s hard to tell a lobsterman how to lobster.

“It’s a start. You’ve got an idea,” Casoni allowed. “I mean, I don’t discount anything, personally, but it’d be a very hard sale to everybody.”

“We have to find a solution, because the whales are still going down,” Martinie countered.

“I know it. We’re well aware of that,” Casoni said.

The debate grew increasingly tense, until Casoni decided he’d heard enough.

“I’m going to move on,” he said. “I got the idea.”

For the most part, though, the day was filled with conversations that lobstermen want to stick around for.

“Never hurts to stay on top of your health,” said Mark Leach, one of dozens of lobstermen who got his blood pressure checked at a booth run by Fishing Partnership. The nonprofit helps fishermen access health insurance and reach economic security, among other services.

Steps away from Leach, lobsterman Arthur Noronha, who fishes out of New Bedford, took advantage of another offering from Fishing Partnership: a rebate on a new lifejacket.

“A lot of guys cannot afford them and they don’t buy them, but it’s worth the money,” Noronha said. “I had two guys fall off the boat. And if they didn’t have the [lifejackets] on, I might have had an accident.”

It’s a reminder that lobstering comes with all kinds of dangers. Working alone, or with one or two others, puts lobstermen at the mercy of an unforgiving environment. And it can be lonely.

“We might bump into someone on the water, have a quick talk. ‘How are you doing? How are the fish?’” said lobsterman Steve Holler, who fishes out of Boston. “Or we get together at the dock, but then we go home and go to bed. It’s a nomadic kind of life.”

But, Holler said, it’s worth it.

“I love it. It’s the thrill of being independent. You are your own boss. We joke around: we don’t play well with others in the sandbox, so we go on a lobster boat by ourselves.”

In Massachusetts, the lobster fishing season begins in May. Until then, Holler, like his fellow lobstermen in this windowless conference room, was looking forward to getting back out on the water.