How small New England cities are standing up to white supremacists

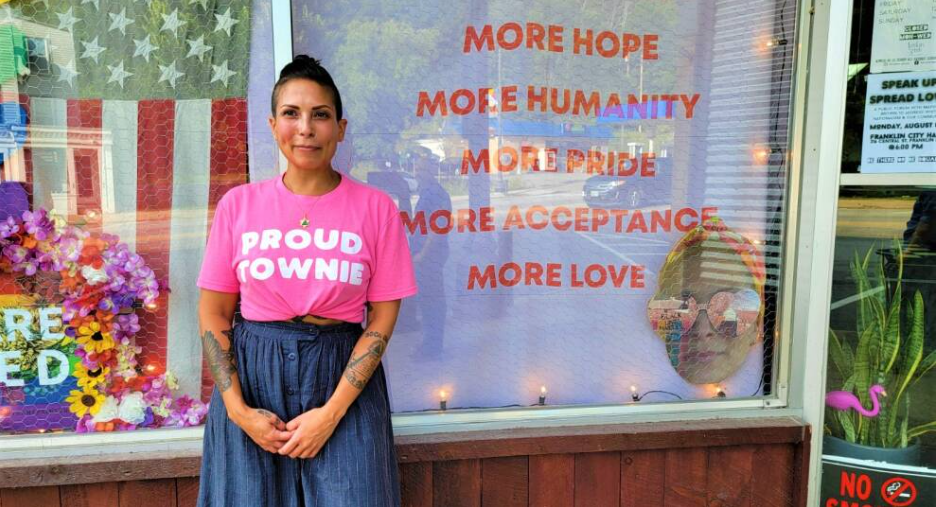

Miriam Kovacs stands in front of her Franklin, N.H. catering business. Kovacs has been a target of online harassment by white supremacists since she made a point of protesting their presence in New England. (Phillip Martin / GBH News)

Two dozen local residents crowded into the city hall in Franklin, New Hampshire, last week to demand that their mayor and council representatives take a more aggressive stance against growing white supremacist activity in the region.

They denounced neo-Nazi groups that have encroached into local council and school committee meetings across the state. Most residents showed up in Franklin specifically to support local businesswoman Miriam Kovacs, who is Jewish and Asian, and has been in targeted on social media by members of NSC-131, one of the white supremacist groups active in the region.

In July, Kovacs took to Instagram and Facebook to denounce a group of neo-Nazis who were demonstrating outside the Kittery Trading Post in Kittery, Maine, holding signs reading “Keep New England White.” Shortly afterward, her catering business, The Broken Spoon, was tagged with a one-star review from someone identifying themself as Rudolf Hess, a clear reference to Hitler’s loyal deputy. Other negative, hate-filled reviews followed.

“They left a lot of Holocaust references,’’ said Kovacs. “Some were as bold as to leave a picture of the train tracks to Auschwitz.”

Concerns about white supremacist activity are becoming increasingly common across New England. Public officials and community organizers have stepped up to confront and combat groups described as “neo-fascists” by the Southern Poverty Law Center — such as NSC-131, the Patriot Front and the Proud Boys — that have become more brazen, holding public rallies, defacing property with supremacist slogans and targeting LGBTQ events.

In the Boston neighborhood of Jamaica Plain recently, about two dozen people came out in support of a drag performer who had been previously harassed by right-wing protesters while providing the popular Drag Story Hours for Kids.

Patrick Burr, alias Patty Bourree, says he is often the target of extremists’ protests. Most recently, NSC-131 rallied outside the historic Loring Greenough House in Jamaica Plain where people had gathered for the children’s event.

“I felt so much gratitude and respect for the people in [Jamaica Plain] who came out to counter-protest,” Burr told GBH News. “Walking past a group of neo-Nazis and then walking past a group of police officers, for me, that doesn’t cancel each other out.”

Burr and other LGBTQ activists, in response to what they perceive as growing street level right-wing extremism, say they are working with anti-fascists as a counterweight.

“There just needs to be a system in place so that if I am in a car driving to story time and I hear that one of these groups has showed up, we don’t have to cancel,” Burr said. “I know I can message so-and-so and they’ll phone tree so that we can have our own community be present. Because that’s what I feel like I need to be safe.”

Frankin residents take a stand

Central Avenue, the main street that runs through Franklin, is dotted with shuttered businesses like the old Regal Theater and a few bold startups including the Vulture Brewing Company and The Broken Spoon. In the brightly colored front window of Kovacs’ catering company, she displays a sign reading “You are Loved” superimposed over the American flag.

“She wears her politics on her sleeve,” said Mark Faro, a Franklin police officer and Kovacs’ close friend. “It’s pretty much just putting big targets on the windows to say, ‘Here I am. This is the place you hate.'”

Police Chief David Goldstein said he reached out to the FBI about the online messages directed at Kovacs. He said his approach to these groups reflects both his decades on the police force and his Jewish heritage.

“I worry about myself,” he said. “I worry about my people. I worry about my communities. I worry about my family and my friends.”

Emergency Franklin City Council Meeting Monday August 8, 2022. (Phillip Martin / GBH News)

Homeless people have set up encampments near Central Avenue, and this tiniest of New Hampshire cities, with a population of 8,741, has not been immune from the opiate crisis in the region. There’s fear that disaffected white youth could be susceptible to recruitment by white supremacists.

Franklin Mayor Jo Brown says residents of this working-class community are fiercely protective of their own. But she and city councilors were still surprised by the number of people who showed up Aug. 8 for an emergency meeting in response to the attacks on Kovacs and the rise of white supremacist activity in the area.

Eleven residents went before a microphone, including Kovacs, who called on the council to pass an official resolution condemning white supremacy.

One speaker described her discomfort seeing two Confederate flags flapping from homes along her route to the meeting. A teacher said the council should take action to show local school children that adults will take a stand against hate. Another speaker said she would like to see a greater police presence “showing proactive support” for communities besieged by white supremacists.

Rainbow crosswalk in Franklin, NH, painted by local school children and target of protest by local conservative parent group. (Jessika Gardner)

Beyond the avowed white supremacists, some local residents also expressed concern about a wave of anti-gay sentiment in Franklin.

In June, some parents went before the city council to complain about rainbow crosswalks painted a month earlier by elementary school children as part of a project to “enhance the city.”

“That was interpreted by a select group as the gay flag,” lamented Mayor Brown. “I seriously doubt the first graders, second graders and third graders were thinking about that as the sidewalks were painted.”

The emergency council meeting was the culmination of efforts by Kovacs and others to get their community to take a stand “against hate,” much as Dover, New Hampshire, had done in late July, when it passed a resolution sponsored by Councilor Robbie Hinkel Condemning Racial and Religious Supremacist Activities.

The meeting ended with a promise to draft a resolution condemning neo-Nazis and other extremists and supporting those targeted by organized hate groups.

“What we’ve agreed to do is to put together a resolution that that will condemn, just as Dover has done, white nationalism,” Brown said. “I will personally contact our federal delegation to get their support as well.”

Business owners find support through social media

Kovacs was not the only one inspired to respond to the white nationalist demonstration in Kittery.

Dresden Lewis, who runs the Nommunism bakery outside of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, learned about the demonstration and used Instagram to call for a counter-protest. She asked people who supported her business to go to Kittery to “reclaim the space for kindness and good and show that, no, we’re not going to keep New England white. New England was never white. And this doesn’t work for me and it shouldn’t work for you.” Dozens showed up, holding signs condemning white supremacy and intolerance.

“You know, I moved to New England from Texas because I wanted to escape a lot of the hate that lived down South,” Lewis told GBH News. “I know that hate groups are everywhere, but I was just maybe hoping that New England would be a little bit more aware.”

Kovacs was not at the Kittery counter-protest, but she and Lewis, who knew each other only on Instagram, formed a bond — and both became targets of local hate groups and their supporters.

Kovacs and Lewis said the social media excoriation by white extremists has backfired.

“Getting tortured by these guys has totally been worth it for us because it’s been great for our business,” Lewis said. “We have people all across the state and into Vermont and Massachusetts and even Maine asking us ‘Where you are located?’”

They also agree they would have taken a stance no matter what the outcome.

“My concern isn’t so much my business. It’s more so my community. Other communities. Not to be dramatic, but, you know, the safety of our nation as a whole, because we’ve seen what can happen,” she said, pointing to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. “You know, not wanting it to happen isn’t enough to keep it from happening. … ignoring it isn’t going to make it better.”