‘Flash droughts’ and weather ‘whiplash.’ Welcome to New England’s climate future

The corn on Dave Dumaresq’s farm is smaller than usual because of the drought. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

To put it bluntly, it kinda just stopped raining this summer. Parts of the northeast that typically get about 9 inches over June, July and August have gotten a fraction of that. Rivers are running low and many streams have gone dry or become a series of disconnected puddles. Lawns are crunchy, vegetation is shriveling and groundwater levels are plummeting.

Dave Dumaresq’s vegetable farm in Dracut, Mass., is located in the epicenter of it all. And it shows.

His boots kick up plumes of fine dust as he walks between garden beds. The corn stalks have turned brown and the ears are smaller than usual. Instead of a carpet of lush green leaves, the potato field is patchy.

Dumaresq, the founder and owner of Farmer Dave’s — a 100-acre mostly organic farm — says that with so little rainfall this summer, he feels like he’s “playing God” with the fate of his plants.

“We’re basically at the point now where we’re selecting which crops to continue to grow and which crops to basically allow to suffer,” he says. The corn falls into that latter category. He staggers the planting and harvesting, and has gotten two decent pickings so far. But the next two are a crapshoot.

“I’m not watering those last two plantings,” he says. “I’m hoping for rain.”

The forecast is not is not in his favor. What little rain he may get in the next week or so will almost surely not be enough to reverse the tide of this summer’s drought.

The U.S. Drought Monitor shows eastern Massachusetts, most of Rhode Island and parts of eastern Connecticut in an “extreme drought.”

Boston, which normally receives 3.27 inches of rain in July, got only 0.62 inches, according to the National Weather Service. Hartford got 2.66 inches instead of its usual 4.17 inches, and Providence got 0.46 inches, a far cry from its usual 2.91 inches.

In a region known for its steady year-round precipitation, climate scientists say acute droughts like this will become more frequent.

Workers install a drip irrigation pipe onto a field at Farmer Dave’s in Dracut, Mass. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Already this summer, farming in New England is a game of risk, a series of on-going calculations and tough decisions. And an expensive one too.

Dumaresq says a drought year can cost him an extra $60,000 to $100,000. He has to hire several extra people to operate the constantly running irrigation equipment.

“So you have the increased labor costs, you have the increased fuel costs, and then you also have the increased maintenance costs and purchase cost of replacement equipment,” he says.

He’s not alone. The Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources says that farmers across the state are struggling with this year’s drought. Many have reported significant crop losses or seen their hay fields dry up.

Mohammad Hannan, who farms on 7 acres in Lincoln, says he’s lost more than half an acre of broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage and beans so far.

“All that stuff is basically gone,” he says. “So it’s a big, big loss.”

Luckily for him, he has other full-time work. He knows others are not so fortunate.

“If I did not have another job, I would be in real trouble right now. So I can imagine for the other farmers who are doing it full time, they are really struggling.”

Many of Mohammed Hannan’s crops have died this summer because he doesn’t have enough irrigation water. (Courtesy of Mohammed Hannan)

This summer’s drought is reminiscent of the 2020 and 2016 droughts. And it’s in sharp contrast to last summer and the summer of 2018 when New England got a ton of rain.

“It’s just crazy,” Dumaresq says. “Yes, we’ve heard that we’re going to see more extremes in the climate, but man, are we seeing it in just this short three-year period.”

Zach Zobel, a scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, says climate change is certainly playing a role in this weather “whiplash.”

As humans have warmed the planet, we’ve changed the atmospheric patterns that shape our weather systems. In a warmer world, weather extremes like severe drought, record rainfalls and heatwaves are getting more extreme.

That’s not to say that drought is a recent phenomenon in the Northeast. Over the last 150 years, UMASS hydrology professor David Boutt says that records show the region tends to get a dry period like the one we’re experiencing this summer about once every ten years or so.

There was a very bad drought in the mid-1960s, for instance, and another in 1980 — during that drought, the town of Amherst ran out of water and UMASS was forced to close and send all of its students home.

But while drought is part of the New England climate, things have changed over the last decade.

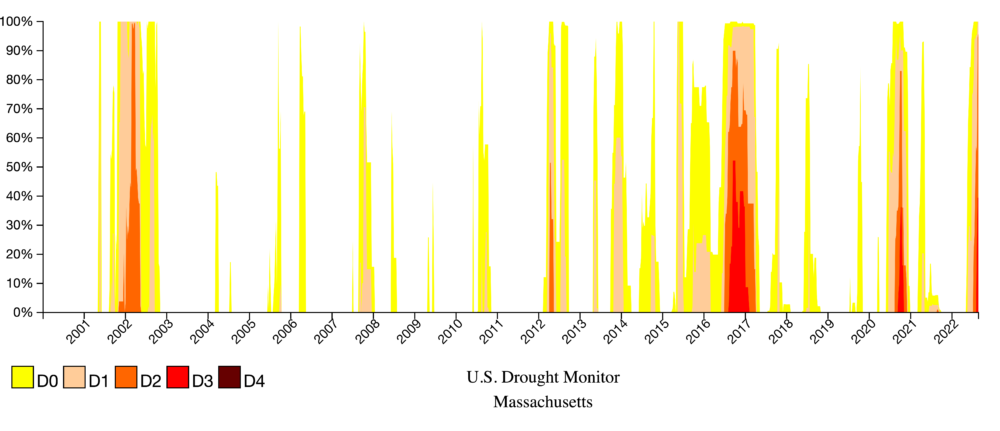

The chart shows the frequency and severity of droughts in Massachusetts in recent year. (U.S. Drought Monitor)

“This kind of year-to-year variability that we see in precipitation seems to be becoming more pronounced,” Boutt says.

Some experts have started calling droughts like the one the Northeast is currently experiencing “flash droughts.” While there’s debate in the scientific community about how precisely to define a flash drought, in general, it’s used to describe a drought that comes on rapidly and only lasts for a short period of time.

“When we think about droughts in the Northeast, they present differently than in the Midwest or in the West,” says Lesley-Ann Dupigny-Giroux, the Vermont state climatologist and a professor at the University of Vermont. They also are more complicated than simply a lack of precipitation.

“It’s not just the water, but it’s also how hot the temperatures are,” she says. Humidity, soil moisture, the rate at which surface water evaporates, even how much water plants suck in through their roots and exhale as vapor — it all matters.

So do rainfall patterns and human development. The Northeast is experiencing more quick and heavy rainstorms because of climate change, and it’s hard for the water from these sudden downpours to absorb into the soil. This means more of it ends up as runoff. Similarly, the more we pave over the ground with impermeable surfaces, the less rainwater makes its way to underground aquifers.

Dupigny-Giroux says it’s helpful to think about the hydrological system as one of supply and demand. Over the summer, demand for water rises as people and plants use more and higher temperatures cause more evaporation. As a result, rivers, soil moisture and groundwater levels all fall. In drought years, the falloff is steeper, and if the ecosystem doesn’t have sufficient time to recover before another dry period, the situation can begin to compound.

“So if I were to say what I think is going on from a deep water perspective, [we’re in] at least a three-year drought,” she says. After the 2020 drought, the rain from 2021 helped, but it probably didn’t completely replenish the lost groundwater.

In other words, when farmers like Dave Dumaresq began their season this summer, they may have already been at a hydrological disadvantage.

Drought, the experts all agree, is a complicated phenomenon.

A pond which has been nearly pumped dry to water a potato crop at Farmer Dave’s in Dracut, Mass. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

“What New England has to worry about are the flash droughts in the summer,” says Zobel of the Woodwell Center. “They are acute in nature and not easy to prepare for. And farmers struggle with the uncertainty.”

Back on Dumaresq’s farm, that rings true. On a hot dry morning in August, he peers over the rocky edge of one of the man-made ponds. Twelve feet down, a small gasoline-powered pump grumbles and sputters as it sucks up the liquid dregs.

The water is only a couple of inches deep. In a normal year, it would be several feet high at this point in the summer.

“In June, it recharged to 8 feet,” he says. “Now we’re down to the point where it only recharges to about 2 feet, giving us only about 6,000 gallons of water to pump. We’ll pump that dry in about two hours. Then we’ll let it sit for two days, and pump another 6,000 gallons or so.”

And in the meantime, he’s just hoping it rains.

This story was originally published by WBUR, a partner of the New England News Collaborative.