Feeling the heat in Greater Boston? Blame historic racist housing practices.

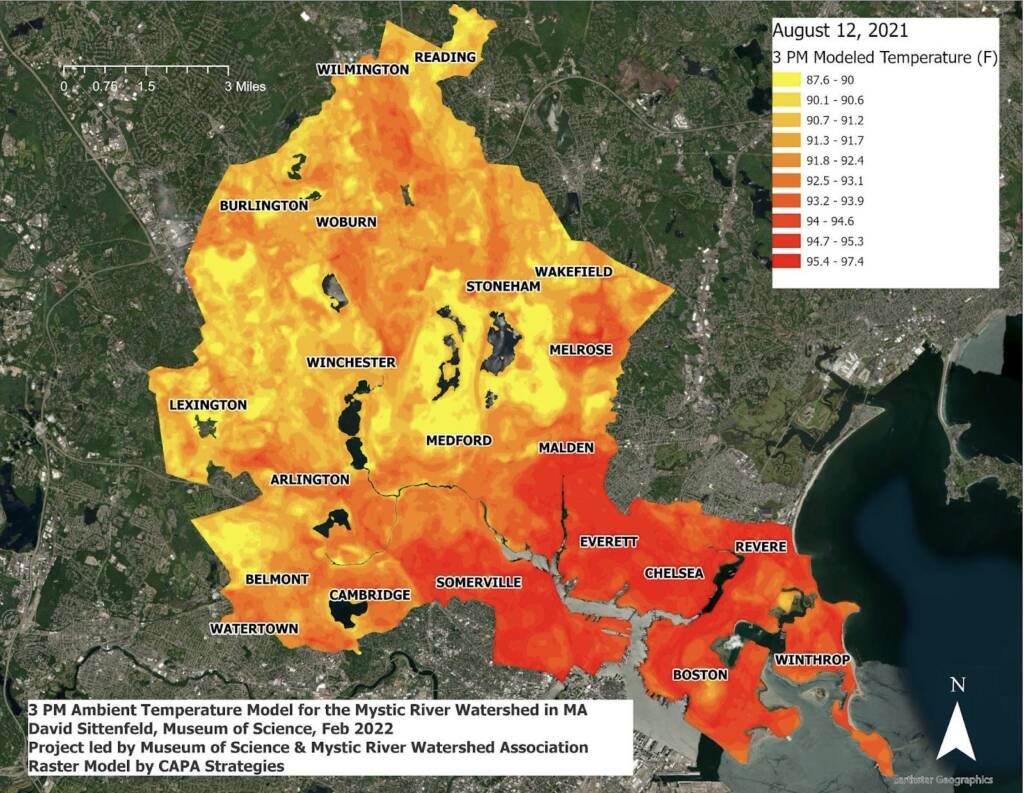

A heat map shows where the Wicked Hot Mystic volunteers found the hottest and coolest ground-level air temperatures on August 12, 2021. (Courtesy of the Museum of Science)

A new study released Wednesday found that extreme heat disproportionately impacts communities that were redlined in Greater Boston.

Wicked Hot Mystic researchers mapped temperatures in the Mystic River watershed — beginning up in Reading, and ending where the river drains into Boston Harbor — to see which areas experienced the most extreme heat. Preliminary findings show 10-degree differences between hot spots, like Mystic Avenue in Somerville and Broadway Street in Everett, and cool areas like the Audubon Sanctuary in Belmont and Middlesex Fells.

The citizen science effort, led by the Mystic River Watershed Association and the Museum of Science, took the work of more than 80 volunteers who traveled across the region during an August heat wave last year to collect temperature and air quality data.

“The hottest areas were overwhelmingly in areas of neighborhoods of color and low-income communities,” said Melanie Gárate, who led the Mystic River Watershed Association’s climate resiliency program during the analysis. “And these areas mirror the areas that were redlined by the government in the 1930s.”

It’s the latest report that shows a direct link between extreme heat and redlining. In a 2020 analysis of 108 U.S. cities, researchers found that 94% consistently showed hotter temperatures in formerly redlined areas within their limits. The decades-long practice from the 1930s until the 1960s of a federal agency rating property areas from “best” to “hazardous” — tied to the race and income of residents — made it difficult for Black Americans to get mortgages, worsening inequity in homeownership.

Areas that were once rated “hazardous” in the Mystic River watershed were, on average, 4 degrees hotter than the “best” zones, according to the Wicked Hot analysis. In Massachusetts, large areas of Malden, Somerville, Chelsea and Everett were rated “hazardous.” Data show Chelsea and Everett are now the hottest cities in the watershed.

Heat kills more Americans each year than any other type of extreme weather, far more than flooding, tornadoes or the cold, lending urgency to a longstanding problem that’s only worsening with climate change.

Workers in sustainability told GBH News the Wicked Hot Mystic results are an important tool to minimize heat on a block-by-block level. David Sittenfeld, the Museum of Science’s manager of forums and national collaborations, said the project’s goal was to offer such a resource to the watershed’s 21 cities and towns.

“It’s really an interesting mix of communities. You think about Winchester, for example, which has a lot of greenspace and the Middlesex Fells,” Sittenfeld said. “And then you look at areas which are historical environmental justice communities, where there is … a lot less tree cover, a lot more impervious surface — in places like Malden, Everett, Somerville.”

Researchers broke out maps for each municipality so that those working on cooling solutions by community can pinpoint the hottest spots in their area.

Darya Mattes, the resilience manager for Chelsea, Revere and Winthrop, pointed out that, while past city planning decisions created today’s hottest zones, it underscores the opportunity for change.

“It informs, at least maybe, our sense of agency and responsibility,” she said. “Like, this is someone’s decision to build these areas in this way. And we can make different decisions now that will make them different in the future.”

A decision that is still having an impact today: the amount of trees in a neighborhood. The poorest-rated areas under redlining have an average of just 3% tree cover today — compared to 43% for the formerly best-rated areas, according to the Wicked Hot Mystic analysis. Planting more trees is a priority for David Queeley, the deputy director for projects with the Mystic River Watershed Association. He’s focused on implementing heat solutions that best work for the towns and neighborhoods who need them.

“What we’re trying to do is develop a — I guess I’ll call it a menu of options and what the costs are,” Queeley said. “So, for example, the menu could include trees, it could include temporary cooling stations, it could include shade structures, it could include things on the policy level.”

One comparatively cool spot, the Belle Isle Marsh, pointed researchers to a simple but effective cooling strategy: getting rid of pavement. Researchers found the grassy land was 7 degrees cooler than paved areas less than a mile away.

“[The marsh] protects the T and neighborhoods from flooding due to sea level rise and increased storm surge. But also now we found that that was one of the coolest spots in East Boston,” Gárate said. “That also gives us an opportunity to think about, ‘Well, even just removing sidewalks or other gray infrastructure in parking lots could actually cool down this area a lot.’”

Pilot programs for more immediate cooling solutions are already cropping up across the region, like a grant-funded program at Everett Public Schools and in Chelsea that’s distributed hundreds of free air conditioners since it launched in 2020.

Some longstanding solutions are being revisited, too. Cooling centers that cities open during heat waves, for instance, are often underutilized, according to Mattes.

“If the cooling center is basically billed as, ‘You can come sit in the middle school cafeteria and it’s air conditioned.’ That’s not very appealing to people,” she said.

Now, Chelsea is offering programming in sites like libraries and senior centers with free internet access to try to entice people to come.

Beyond short-term solutions, communities are bracing for several decades of increasing heat. The Mystic River Watershed Association is taking steps now to find the long-term solutions residents will use on the backdrop of the Wicked Hot Mystic results. It hired two new staff members this year, including Queeley, to specifically drill down on community-led cooling solutions.

“They’re going to start to get into the nitty gritty of: what are the priority areas for people living in these zones?” Gárate said. “Is it public transportation areas that are not very well shaded or cooled off, where people are standing outside for long periods of time? Is it areas around schools and community health centers?”

Renovations to public spaces like parks and bus shelters are providing opportunities to make cities more resilient to heat by adding more tree cover and shade, according to Mattes.

“All municipalities do those updates anyway,” she said. “And we’re just trying to keep heat in mind as we’re doing them to ensure that the new designs are more heat-resilient than the old ones.”

This story was originally published by GBH News, a partner of the New England News Collaborative.