Counting The People Who Are Homeless — Including The Young

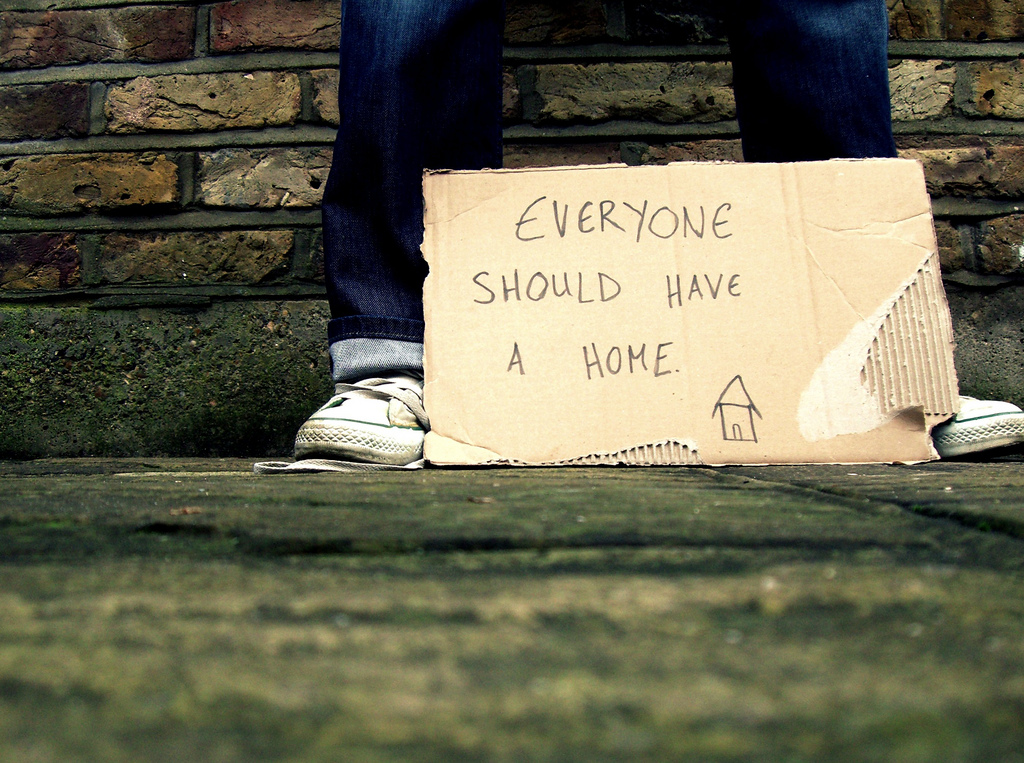

Photo by scribbletaylor / Creative Commons

OPINION

On a cold and rainy night in January, about 70 volunteers gathered in the hall of First Presbyterian Church in New Haven for a ziti dinner, a quick training and a lot of encouragement.

Every year in January, a census is taken among people who are homeless. The Department of Housing and Urban Development requires it when organizations receive funds from the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Grants program. Known as the Point-In-Time Count (or PIT count), the survey is meant to measure successes, but also provide direction for future funding in states’ efforts to end homelessness.

Already, states like Massachusetts and Connecticut have made incredible strides among veterans and people who are chronically homeless, but there’s more work to be done.

Statewide during Connecticut’s PIT count this year, some 400 volunteers fanned out to count people who aren’t housed. People who are living in shelters are counted every year. On odd-numbered years – like this one – volunteers attempt to count people who are sleeping rough – under bridges, in abandoned buildings, and in other places not fit for human habitation.

Preparing for the count, George “Bud” Mention sat off to the side at the church, awaiting his assignment. Mention is a job coach at Marrakech Inc., a non-profit that for nearly 50 years has provided residential and training support to people with disabilities.

“This is what I do,” said Mention, who has been with the organization since 2015. “My job is about helping.”

Wherever the survey is taken, the goal is the same: Find and record everyone who is homeless. In small cities like Chelsea, Mass., volunteers at an overnight count that took three and a half hours found 16 people living on the streets. In 2016, the Vermont PIT count showed a 28 percent decrease in the number of people who are homeless since 2015, which was the nation’s biggest decrease that year. The results of this year’s Vermont count will take a while to compile.

The PIT count has evolved significantly since it was introduced in the 1980s, said Lisa Tepper Bates, executive director of Connecticut Coalition to End Homelessness. This year, Connecticut volunteers and others who participated in the count used a phone app that helped with accuracy, and volunteers also conducted a week-long youth count. Youths who are homeless are particularly difficult to find. They’re good at existing under the radar, far from prying eyes and social services they may not trust.

“Accurate data as close to real-time as possible is an important tool in our work,” said Bates. “Our successes to date have hinged on tracking data accurately in our system, and using the data to target resources.”

Although figures won’t be published for a few months, this PIT count feels particularly weighted. The new president has shown little interest in homelessness. He nominated a HUD secretary who has no experience with the complexity of housing in America. There is more than a little concern that we could see a return to the bad old days, when government policy helped create a scary spike in homelessness.

At least in Connecticut, there’s appears to be a commitment to stay on task. Gov. Dannel P. Malloy recently released his $40.6 billion biennial budget that, according to Bates, appears to maintain the state’s programs to end homelessness.

“We know – and the governor understands — that these investments save our communities costs they will incur in our hospitals, schools, and emergency services when homelessness needlessly persists on their streets,” Bates said.

Certainly in the early ‘80s, New England experienced record homelessness. People teetering on the edge of homelessness saw deep cuts as then-President Ronald Reagan slashed funding to federal assistance programs that helped the working poor.

Meanwhile, housing costs were rising, and housing options like single-room occupancy hotels — SROs — were shrinking. In an effort to improve cities, developers tore down the old flop hotels and replaced them with housing that those former SRO residents could not afford. This while reformers closed or greatly reduced the beds in state hospitals.

Housing prices continued to climb in many parts of New England. Between 1980 and 2003, for instance, Massachusetts saw the nation’s largest larges percentage increase in housing prices, according to a 2004 study of that state’s housing affordability.

Advocates and activists have worked hard to provide adequate housing for people who have been living on the streets. A swipe of a pen could set those efforts back.

Back at the New Haven church, Tasha Peters sat awaiting her orders. Peters is an outreach/engagement worker and case manager at Columbus House, a New Haven non-profit that provides shelter and an array of housing services for people who are homeless. She was the night’s Team 9 captain. As an outreach worker, she knows these streets. The next day, she’ll go back out and do outreach.

Last year, her team didn’t find any one outside. She expected the same on this night. People who can find a way to sleep inside generally find a way to on raw nights like this, she said. It will be catch-as-catch-can.

In all, volunteers found 56 people outside in New Haven, said Alison Cunningham, Columbus House’s executive director.