Closing Homeless Shelters For The Right Reasons

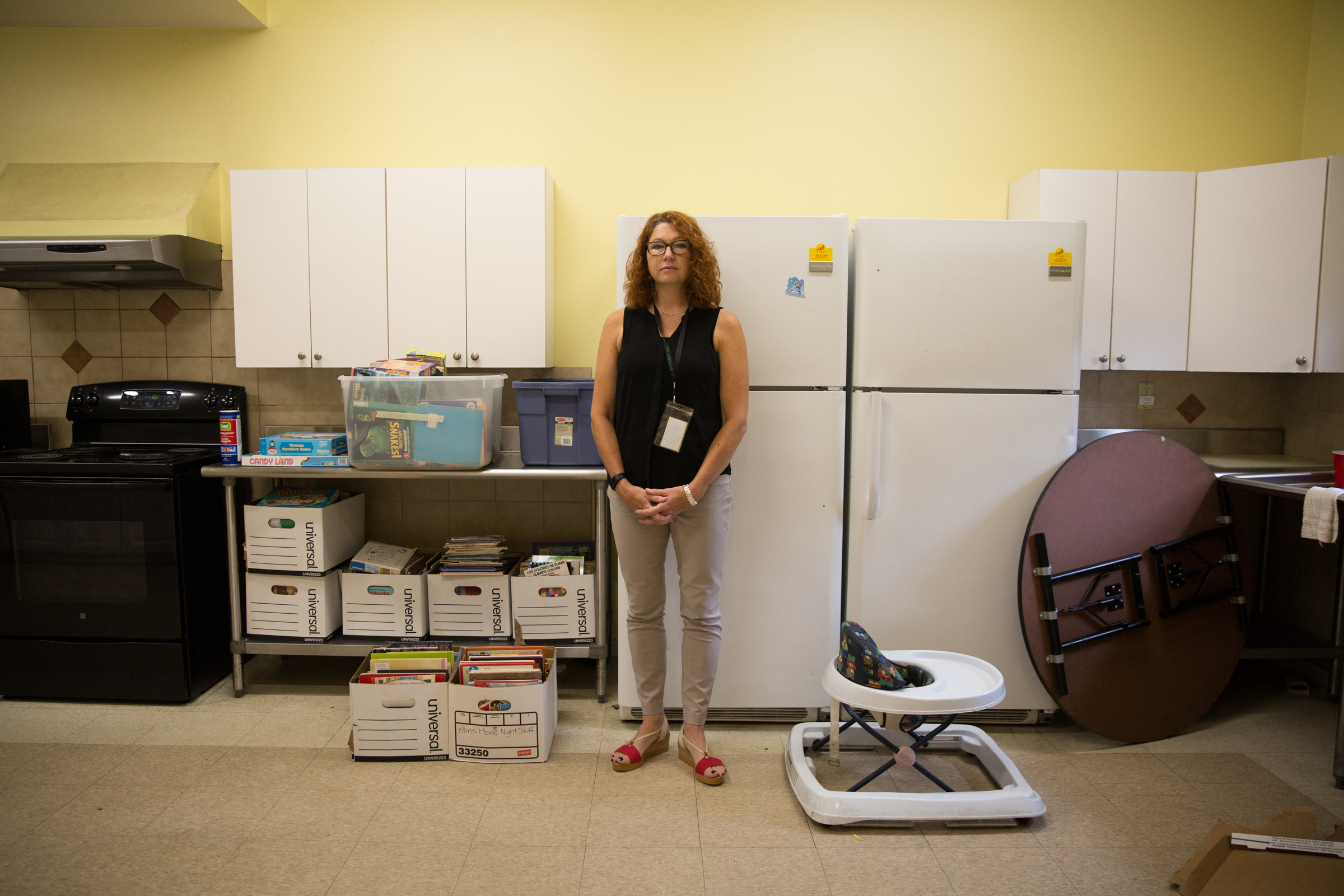

Kellyann Varley Day, CEO of New Reach, in the former Careways Shelter. The shelter closed this summer after 27 years of operation. Photo by Ryan Caron King for NENC

This summer, the people at New Haven, Connecticut’s Careways Shelter for Women and Children, made a stunning announcement. After 27 years, the 10-bed emergency shelter’s doors would close – once the shelter residents had been placed in either temporary shelters or permanent homes.

For the past few years, the emphasis among organizations that work with people who are homeless is to do precisely this – house everyone and close the shelters. But this was different. Careways wasn’t closing because it had accomplished its mission. It was closing because of a budget deficit created by a variety of factors that, on the surface, have actually improved the housing system in Connecticut.

These days, shelters in New England face complicated challenges. The cost of running shelters – once the purview of churches and other faith groups – has increased exponentially. In the last few years, federal agencies such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development have required increasingly sophisticated data in order to measure the success (or failure) of various programs. And that oversight is a good thing, but it has meant that shelters must spend more technology, and staff.

Meanwhile, in the past few years, the focus for funding – public and private — has been on solution-based programs. Millennials, in particular, don’t tend to donate to organizations such as a shelter. They want to donate to causes.

Add to the already complicated world of financing the state budgetary woes of Connecticut, and Vermont, and lower-than-expected tax revenue in Massachusetts. None of this bodes well for social services.

“We have been looking at and talking for years about the fact that we want to invest in housing,” said Kellyann Varley Day, CEO of New Reach, which operated the shelter. “We don’t want to invest in more shelters; housing is better for people.”

But shelters, said Day, are an important part of a continuum that moves people who are homelessness into permanent homes. Without that starting point, how do you plug people in to Connecticut’s system that ultimately will get them housed?

“Shelter is part of the continuum and safety net for people that we serve,” said Day. “We’ve not done a good job at looking at every part of our continuum and making sure each part is solid.”

All of that means achieving a balanced budget among cash-strapped shelters can be an unattainable dream. Operating with a deficit only works for so long, and that’s true around New England. Youth On Fire, a 17-year old drop-in center for homeless youth based in Massachusetts’ Harvard Square, find themselves in financial crisis. That center is eyeing a $300,000 shortfall after the state cut funding. The shortfall means the shelter won’t be able to operate next year, according to AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts, its parent company.

Though Careways had been operating in the red for a while, the decision to close did not come easily, said Day. Careways opened when the homeless crisis was just starting to take Connecticut by the neck, and providing services for shelters for families experiencing homelessness remains a priority.

Despite incredible strides made by Massachusetts and Connecticut to end homelessness among veterans, and among people who have been homeless for years, every night, Day said, 30 families are homeless in New Haven County.

“And there’s an empty building,” said Day. “Shelters are safety nets. Shelters are tonight. There’s a family who is homeless, and we need to keep them safe tonight. When a person is suffering a crisis, they hit that proverbial bottom, there needs to be a continuum of services to get them back up.”

An empty room in the former Careways Shelter in New Haven.The cost of running shelters has increased exponentially. Photo by Ryan Caron King for NENC

That continuum is overloaded already. Another New Haven shelter for families run by Christian Community Action also faces budgetary challenges, though the executive director, the Rev. Bonita Grubbs, told a local newspaper that CCA is “holding our own.”

“This is not just something that we woke up one morning and said, ‘Oh my God, there’s no enough money for the shelter,’” said Day. New Reach operates two other emergency shelters, in addition to 60 units of housing, plus a wide variety of other programs geared toward a vulnerable population. But “I would not be a good steward of our private or public dollars if we do continue to operate a program that we knew was bleeding out and put all our other programs at risk. It’s a very heartbreaking decision, and a difficult one that our organization made.”

Day said that all Careways clients had been placed elsewhere by mid-August. Some were placed in permanent housing, and others went to other shelters. Their stories could end happily, but for smaller programs like Careways, the future remains uncertain.

“That’s my fear,” said Day. “We are all waiting, smaller programs, and while they’re waiting they may find themselves having to shut their doors. That’s my fear. There’s serious anxiety with clients and staff. Families that we serve have serious anxiety about what’s going to be available for them.”