Climate change could drive migration to New England. Some communities are starting to plan.

Cornell professor Linda Shi talks to an audience in Keene about climate migration, May 17, 2023. (Mara Hoplamazian / NHPR)

As climate change fuels extreme weather and rising sea levels in the U.S. and across the globe, parts of New England could become havens of safety for those fleeing fires, heat, and floods.

Making room for more people was the theme of a conference held in Keene this week, where academics, municipal officials, and advocates from across the region gathered to talk about preparing for migration due to climate change.

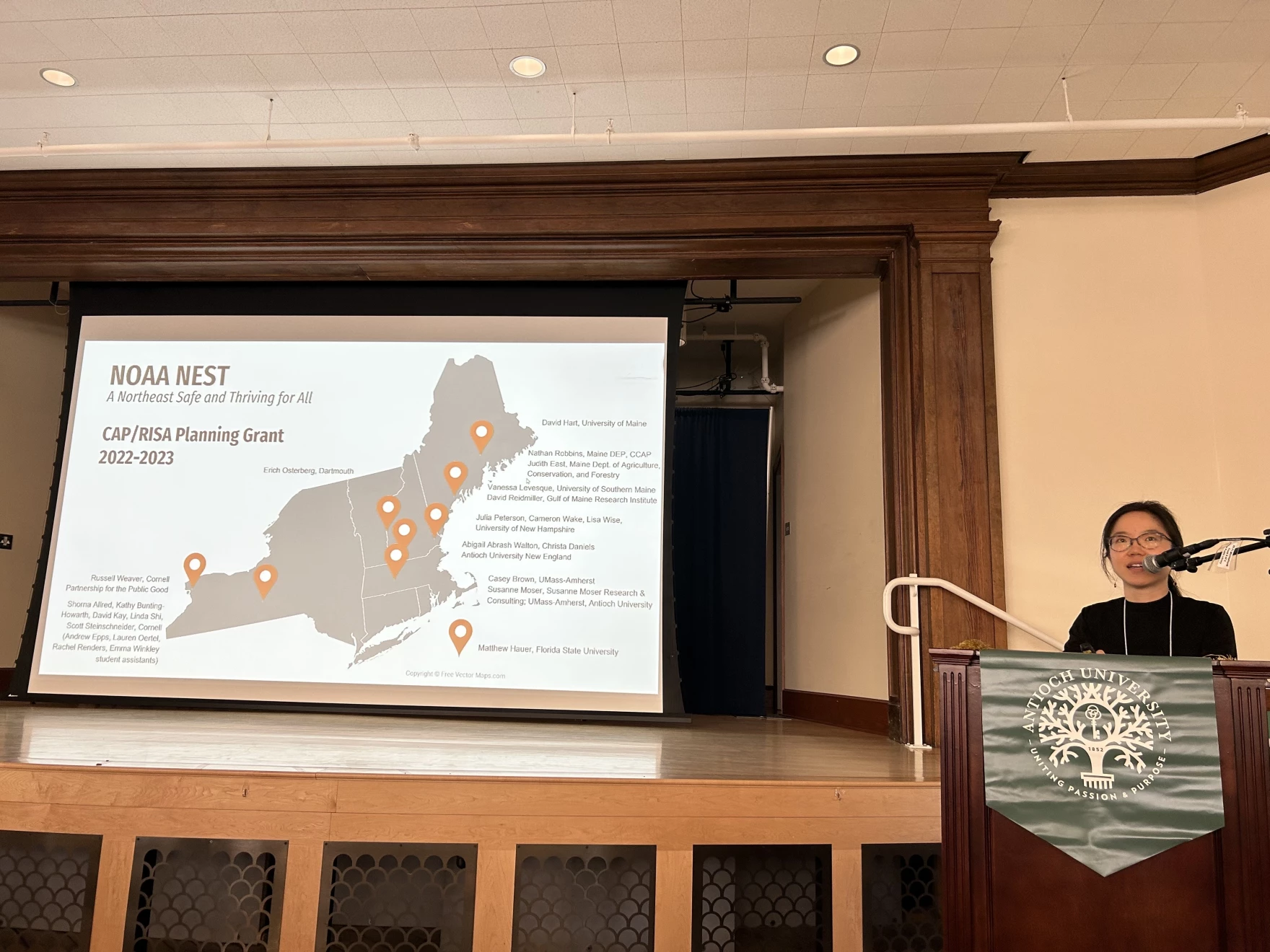

The event focused on research from a new project funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) called “A Northeast Safe and Thriving for All,” which explores equity and justice during climate migration.

Linda Shi, a professor at Cornell and lead researcher on that project, told the audience that though New England is more protected from the harmful effects of climate change than other places, people in the U.S. have tended to move to places that are less resilient, often based on the availability of housing, jobs, or family networks.

“There is a major gap between the ecological approach of what is possible and the realities of where people are actually choosing,” she said.

About 1.7 million people were displaced by disasters in the U.S. in 2017, Shi said.

That same year, 68.5 million people across the globe were forcibly displaced, about a third of them due to sudden weather events, according to the Brookings Institution.

Climate demographers are working to get a better sense of the numbers of people moving, or people projected to move in the future, due to climate change. Shi says those numbers aren’t coming soon, and may never predict what will really happen with migration.

But, she said, that means communities have a choice about whether they want to attract climate migrants and make room for them.

“If people actually do want to attract people, they are going to have to put in significant efforts to make the infrastructure, the housing and the people here actually be one that would be able to accommodate significant numbers of people,” she said in an interview.

Shi said though climate migration may seem like a new challenge, it illuminates problems in social and physical infrastructure that have been around for a long time.

“It is actually a very old issue, and it is something we really have to pay attention to: all of the current inequities that exist in communities in terms of what makes them unwelcoming, unaffordable, inequitable,” she said.

Some cities and towns in New Hampshire, like Nashua, have already started taking climate migration into account when planning.

Keene Mayor George Hansel said for that city, housing would be the biggest challenge.

“The only thing that’s limiting our population growth is the availability of housing right now. That pressure is going to be on Keene for the foreseeable future,” he said. “Our planning staff realizes that they’ve got a large burden that they have to bear because we have to lead this whole community through a period of change.”

Hansel also said residents’ attitudes toward change could also pose a challenge.

“There are people that have lived in this community and they just want it to stay exactly the same for the rest of their time here. And they will fight for that,” he said.

Other participants noted the importance of infrastructure like energy, food, and water and waste systems.

“When we’re talking about resiliency, it’s like, how many more people can be pooping into your sewer system?” said Alex Beck, who works with the Brattleboro Development Credit Corporation.

Eva Castillo, the director of the New Hampshire Alliance for Immigrants and Refugees, told the audience that inclusion is an integral part of making room for climate migrants.

“The process of decision making and welcoming is big on including people. When we decide for other people, when we do not include everybody in the decision making process, in the way we design things, then they don’t work for everyone,” she said.

Shi, the Cornell professor, said more information is needed on climate projections, peoples’ reasons for moving, and issues like zoning and land use as conversations about climate migration continue. She said it’s important to start planning.

“If corporations and speculators get in front of that, then they are going to buy up the land and territories and make affordable housing provision so much more challenging once people are coming around to the idea that we need to plan for growth,” she said.

But, Shi said, historical migrations show that building social and physical infrastructure for these kinds of movements takes decades, and the effort to manage climate migration will be generational.

“Since change is going to happen, it falls on us to imagine and to figure out what kind of change we actually want to have,” she said. “Whether or not that means the Northeast is going to become a really vibrant place as it once was throughout the region – I think that remains to be seen.”