Why A Commercial Fisherman Turned To Restorative Ocean Farming

Bren Smith began his career as a commercial fisherman, but now is the owner of Thimble Island Oyster Farm, a 3D restorative ocean farm in Connecticut. He’s also the author of the new book, Eat Like a Fish: My Adventures as a Fisherman Turned Restorative Ocean Farmer.

But what exactly is a “3D restorative ocean farm?” Smith says it might just be the future of working on the sea, and he says it’s a lot different than the life he used to live.

Interview Highlights

These highlights have been edited for length and clarity.

Bren Smith: I shifted from a commercial fisherman on the Bering Sea in Alaska to a salmon fisherman, and then shellfish. And the shift from fishing to farming was actually kind of unsettling and boring for me. As a fisherman, I always chased fish you know, further and further out to sea. And it was, it was an adventurous life. And farming is much more meditative, careful, slower. So that was a challenge. That said, the similarity is, they’re still jobs you can sing songs about, right. They’re jobs with meaning, of the pride of helping feed the country. You own your own boat, no boss, it’s a self-directed life. So, although I don’t chase and kill things anymore, I still have that part.

John Dankosky: The life of the fisherman is hard. It’s dangerous and you’re chasing this living thing. How did your relationship with that work change as you grew older and you learned more about the work that you were doing?

Yeah, you know, I showed up, especially in the Bering Sea, I just loved it, right. The wild humility of being in, you know, 40-foot seas. The hours I love, 30-hour shifts with 13 other people in the belly of a boat. But as I eventually went back to college for a while and then kept on going back to Alaska, I learned the context that I was working in.

I was working in the height of an industrialized fishery tearing up whole ecosystems. And most of the fish I was catching was going to McDonald’s for the fish sandwich. So, when I faced that context I realized I loved my job, it was an incredible job, but it was extractive and there needed to be some changes. But, you know, it wasn’t this, I wasn’t an environmentalist. It was really a question, a realization that, oh, for me to make a living on the ocean we had to become stewards of the ocean.

Why do you say you weren’t an environmentalist? Why is it an important thing for you to say?

I mean, and this is extremely relevant, I think, for climate change. So it’s been framed by environmentalists forever about the bears and bees and birds and really about protecting the natural world, but most of us who work, we experience it as a kitchen table issue, right. There are gonna be no jobs on a dead planet. When the cod stocks crashed in Newfoundland, back where I was from, 30,000 people thrown out of work overnight. The biggest layoff in Canadian history. And it was amazing to watch a culture and an economy built up literally over 100 years just disappear over, overnight. And that’s when I, you know, this idea that we need to make a living on a living planet, that goal had to motivate all of us from all different aspects. Whether we’re, you know, foodies who love seaweeds and oysters, whether we’re environmentalists that really care about the birds or the bees, or those of us that, you know, work in the water.

Explain to people who don’t know what aquaculture exactly is.

So, aquaculture is, really, farming the ocean. And traditionally it’s always been about farming fish. And the reason is, you know, we fish and we wipe out the fish and then we decide, OK, we’re going to grow what we’ve wiped out because that’s what the market demands, that’s what tastes demand. So, it’s traditionally been about growing, you know, salmon, tunas, things like that.

That’s what people like to eat.

Yeah, exactly. What I found when I arrived on the salmon farms because that was supposed to be the great hope: jobs for fishermen, we’re going to feed the planet, all this sort of stuff. Instead, it did exactly what land-based industrial farming did, but in the sea. Monoculture using antibiotics, pesticides, polluting local waterways. I mean, really growing neither fish nor food. Iowa pig farms at sea. So, instead of looking at the ocean as this unique agricultural space and asking the ocean, OK, what do you want us to grow. We just grew around existing wild tastes and I think that was a mistake. So, after I left the salmon farms I didn’t know what I’d end up doing. But that was a journey of really asking the ocean, OK, what makes sense.

What was the ocean telling you? What were you learning that the ocean wants humans to grow?

You know, I ended up here in Long Island Sound in, sort of, this full circle of my family. I never expected it. Lived in an Airstream trailer in Guilford for, was supposed to be about six months, it ended up being seven years. Which, uh, the first six months were great, by the way. And so, I started with oysters and I was a terrible farmer. I ran a death camp, right, killing millions of oysters because I didn’t know how to farm. But, what oysters taught me was that if you grow things that don’t want to swim away and you don’t have to feed, it’s a game changer. Because we have all these species that can grow just with nutrients that are in the water, that we have too much of, too much nitrogen, too much carbon, too much phosphorus, and grow with sunlight. It becomes really a simple, elegant and, quite honestly, cheap way to grow food.

The market for oysters has changed over our lifetimes. The idea that you could farm oysters on Long Island Sound or up in Maine comes from the fact that people really do want to eat them and pay some money for them.

What’s amazing in American culture is that food has become central. You know, I grew up in the ’80s on the fish stick and the fish sandwich at McDonald’s, which, you know, I love those both. I get my lonely moments and I’ll go to a parking lot and gobble a couple of fish sandwiches at a McDonald’s. But, food has become a central sort of discussion point, community anchor, and it’s just amazing to see. And oysters were one of these agents of sustainability that we could eat and actually changed, then rearranged the plate to create a sort of environmental cuisine, or what I think of as a climate cuisine.

Now, I think one of the key things from a farming perspective is to always move beyond monoculture. Mother Nature abhors monoculture. She introduces disease and all sorts of things. So, the great thing about the ocean is we can do polyculture. There are 10,000 plants in the ocean, hundreds of kinds of shellfish. So, the question for me was, let’s take 20 acres and figure out all the different things we can grow in those 20 acres that are, you know, indigenous to Long Island Sound.

Describe for our listeners what 20 acres of polyculture in the ocean looks like. What’s in there?

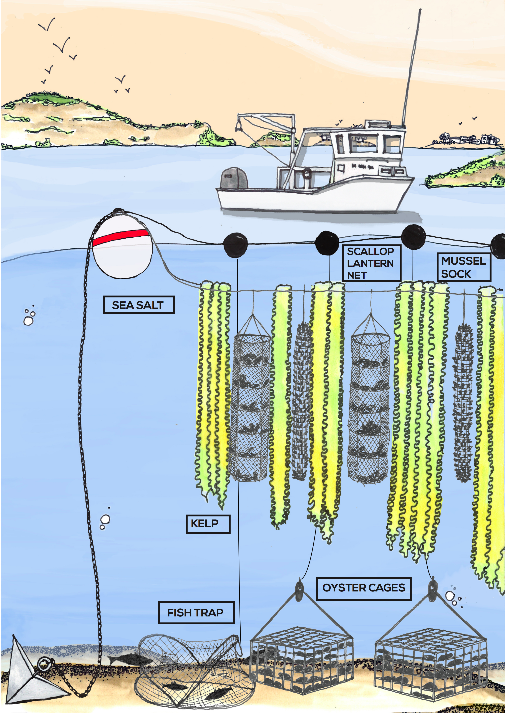

So we call it restorative ocean farming. And imagine an underwater garden where you’ve got anchors down the bottom and then just buoys up to the surface. And then horizontal lines about eight feet below the surface and from there we grow our kelp vertically downwards. We attach mussels and something we call mussel socks, scallops, and lantern nets. And then my farm, I’ve got oyster cages sitting on the sea floor and then clams down in the mud. And this sea basket approach of growing year round, different species that diversifies risk for the farmer.

The interesting thing is because it’s all underwater and all it is is just rope scaffolding, that’s really cheap. You just need like 20, 30 grand to start and get up and going. But it also has a really low aesthetic impact, so you can boat, fish, swim over the farm. Some of the best fishing in the whole area, I’m in the Thimble Islands, is right on my site and has a low aesthetic impact and that’s really important, right. Our oceans are these beautiful, pristine places and instead of massive fish pens, we can have these aesthetically low impact farms.

Is this something that can be done at a greater scale? And is there a risk of getting back into the large scale kind of factory farming that you talk about, either in the aquaculture you used to work in or in pig farms in the Midwest?

That’s exactly the core question and it kind of keeps me up at night because we’ve had a huge amount of success. What I did was I founded Greenway, which is a non-profit based right in New Haven, and we’re training the next generation of ocean farmers. And we’re working in Alaska, California, Pacific Northwest, New York. We just put our first farms in and, of course, throughout southern New England. And we have requests to start farms in every coastal state in North America and 20 countries around the world. There’s like a tsunami of interest. And so, one of the questions we’ve had at Greenway is, what does scale look like? Because in the era of climate change, every solution we come up with we have to ask, is it scalable? We’ve got 30 years to address the food crisis, the climate crisis, things like that. So, according to the World Bank if you were to take less than 5 percent of U.S. waters, you could grow the equivalent protein of 3 trillion cheeseburgers and soak up 120 million tons of carbon. So, we can really scale this.

But does that look like thousand-acre farms out at sea? Are these sort of banana plantations? And for us, it’s no. What it looks like is a greenway reef where we have networks of 50 farms, all 20 to 30 acres or so, a seafood hub and a hatchery in a disadvantaged neighborhood like Fairhaven, a neighborhood in Connecticut, and then a ring of entrepreneurs. And then you replicate that reef up and down the coast. So you scale through networked production. There’s a huge community benefit because there are lots of small businesses rather than one vertical. I’ve got a section on the principles of restorative ocean agriculture in the book where I’m trying to lay out, okay, what does a new economy look like? Listen, the ocean is a blank slate. And that’s exciting because we can take all these lessons from industrial aquaculture, all these lessons from agriculture and move out in the ocean and sort of do food right. Build something from the bottom up that makes sure that beginning farmers have access to land and makes sure that social justice is woven into the DNA of this economy to make sure that the benefits don’t go to the top but go to benefit everybody in the community.

This is an edited interview from the June 13, 2019 episode of NEXT. You can listen to the entire show right now. Find out when NEXT airs throughout all of New England.