A shortage of special education staff leaves many students without services they need

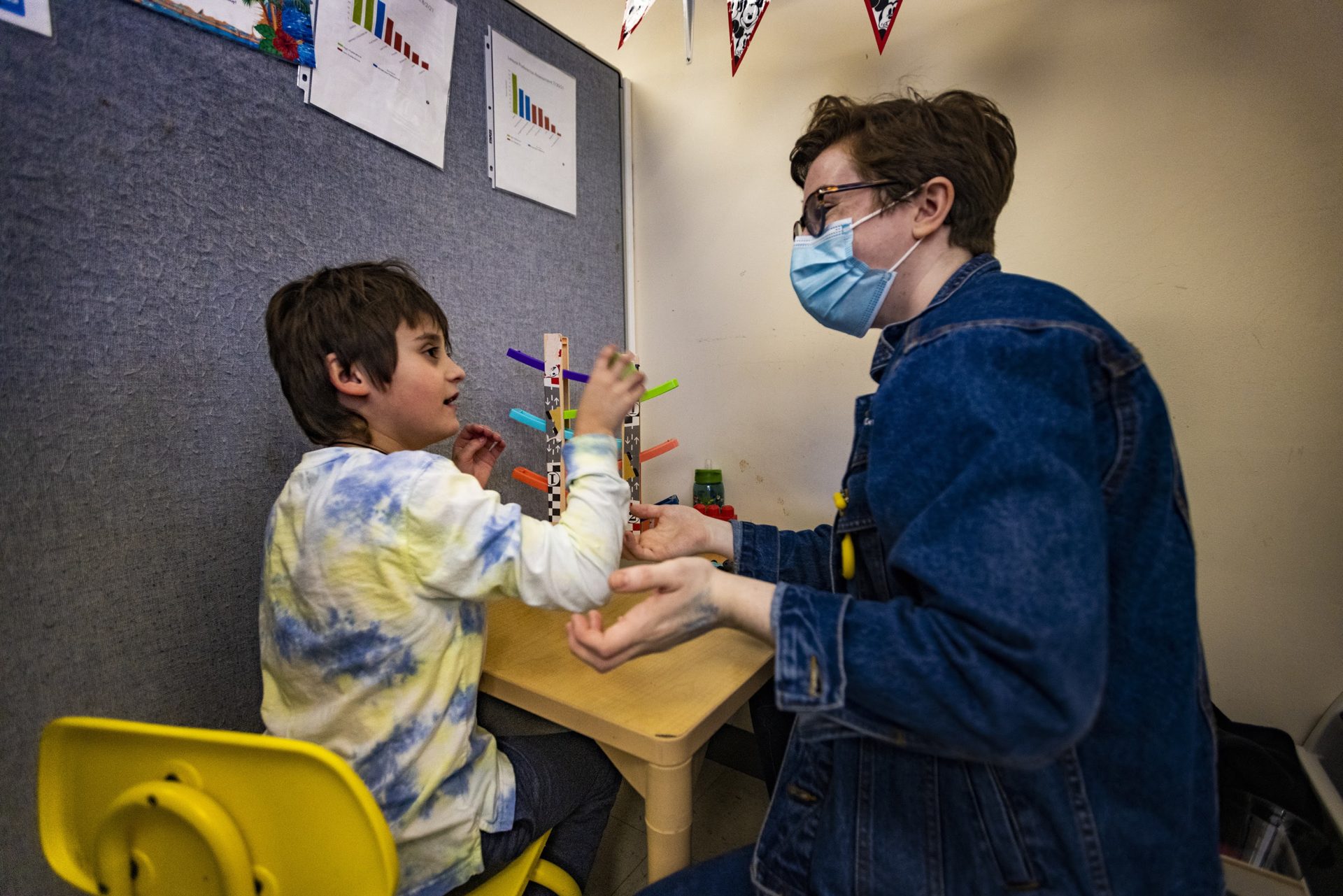

Teacher Kate McDermott plays an imitation game with a student at the New England Center for Children in Southborough, Mass. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Sara Harold describes her son, Finn, as a vibrant 3-year-old.

“He loves running, jumping, exploring how things work and the intricacies,” said Harold, as she watched him play with a set of magnetic blocks. “While he has very few words, he can make his presence known.”

Finn’s mom does most of the talking for him right now because he has a speech delay. It’s something Harold noticed when Finn was about 2 years old.

Harold signed Finn up for a speech therapist who went to his daycare. But that was pre-pandemic. When his therapy went online, Finn’s progress pretty much stopped.

“As you can imagine a 20- to 21-month-old will not sit in front of a Zoom for long,” Harold pointed out with a rueful laugh.

Without therapy, Finn regressed. As soon as schools and businesses began reopening, Harold says she re-started her search for services. But she kept hitting road blocks. She’d call up an organization and set up an assessment.

“I thought everything was going swimmingly, and then at the end of the session I’m like, ‘Ok great, when can we start?’ ” she remembered thinking. “And then I’m told, ‘We don’t have enough staff.’ “

Another facility told her it had an 18-month waiting list because it was also short staffed.

Eventually, Finn was diagnosed with autism, and his symptoms qualified him for services at Boston Public Schools. But Harold soon realized BPS had staffing issues too.

For the rest of this story, including the audio version, please visit WBUR.org.